The global industrial narrative regarding sustainability has converged almost exclusively on the concept of circularity, emphasizing the endless recycling and reuse of components. While this model serves consumer electronics well, it often fails to address the brutal physical realities of high-scale compute and energy infrastructure. Operators and architects now face a fundamental tension between the cradle-to-cradle promise and the thermodynamic reality of system degradation. Designing for permanence suggests that the most sustainable component is the one that never requires replacement, recycling, or re-entry into the supply chain. This paradigm shift prioritizes structural longevity and restraint over the iterative churn of green hardware cycles. By focusing on durability, system builders can mitigate the massive energy overhead associated with the reclamation of materials.

Some industry observers and system designers contend that an overemphasis on circularity can unintentionally enable shorter product lifecycles, particularly when recyclability becomes a substitute for durability. In this view, designing systems primarily for end-of-life recovery may reduce the incentive to engineer for extended operational longevity, reinforcing frequent replacement cycles rather than resisting them. This critique does not reject circularity outright but questions its sufficiency as a sustainability strategy for long-lived infrastructure.

Thermodynamics and the Fallacy of Infinite Reuse

The second law of thermodynamics dictates that every instance of recycling involves an inherent loss of energy and material quality. Within the context of high-performance compute, the degradation of thermal interface materials and semiconductor packaging makes circularity a diminishing return. Designing for permanence acknowledges these physical constraints by over-engineering systems to operate well below their thermal thresholds. This restraint in operational intensity extends the mean time between failures (MTBF) significantly, reducing the need for intervention. System architects are beginning to prioritize passive durability, where the physical structure of the system handles heat and stress without mechanical assistance. By reducing moving parts, operators can achieve a level of permanence that circular models cannot match through logistics alone.

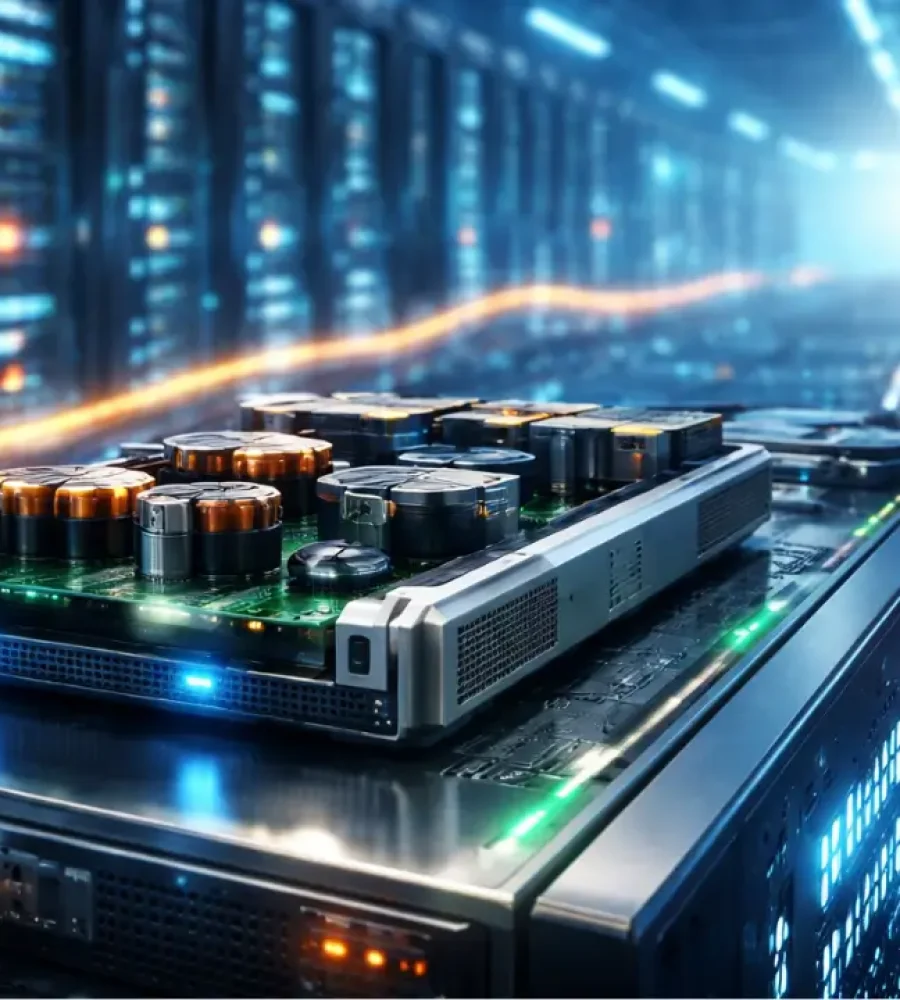

A permanent architecture requires a fundamental rethink of power delivery systems, moving away from modular swap-out components toward monolithic, high-durability cores. Modular designs often introduce more points of failure through interconnects and connectors, which are the most common sites of mechanical fatigue. By consolidating power architecture into more robust, integrated units, engineers reduce the complexity that leads to premature system retirement. These permanent systems demand a higher initial capital expenditure but offer a lower total environmental cost over a twenty-year horizon. The industry must move beyond the three-to-five-year refresh cycle that currently dictates the rhythm of global compute deployments. Consequently, permanence becomes a hedge against the volatility of raw material markets and the high carbon cost of global shipping.

Physical Constraints and the Restraint of Scale

Designing for permanence requires a deliberate exercise in restraint, particularly regarding the density of compute clusters and power distribution. High-density environments accelerate the aging of components through localized heat pockets and ionic migration within silicon. Operators who choose to spread compute loads over larger physical footprints can leverage natural convection and lower voltages to preserve hardware. This approach contradicts the current industry trend toward hyper-density but offers a more stable path toward long-term infrastructure viability. Restraint also applies to the software layer, where optimizing for legacy hardware prevents the forced retirement of perfectly functional physical assets. When systems are designed to be permanent, the software must be architected to respect the fixed limits of the underlying hardware.

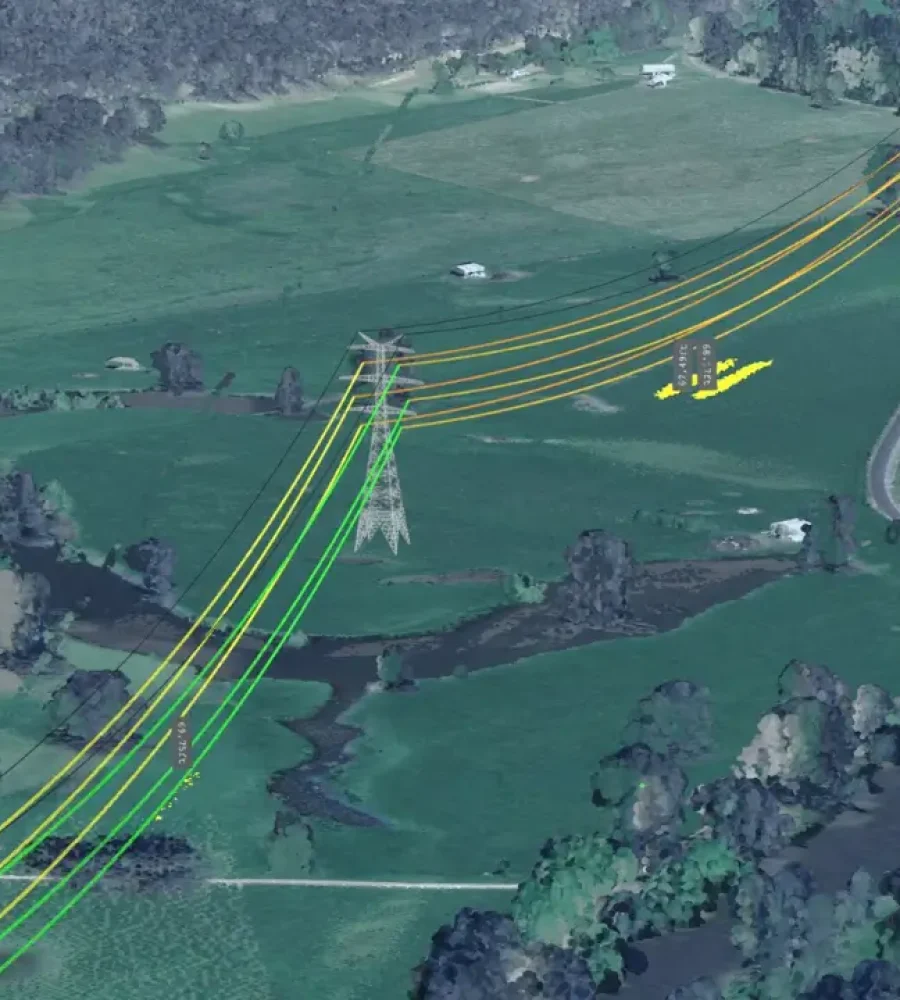

The physical constraints of energy transmission also dictate a move toward more permanent, localized power generation for massive compute clusters. Relying on aging, centralized grids introduces inefficiencies and surges that damage sensitive power electronics over time. Permanent design integrates hardened energy storage and generation directly into the facility’s structural footprint, creating a closed loop of stability. These fortress architectures are designed to withstand environmental stressors that would typically trigger a hardware refresh cycle in standard facilities. Architects are now utilizing materials like advanced ceramics and specialized alloys that offer superior resistance to corrosion and thermal expansion. This focus on material science ensures that the physical housing of the system outlives several generations of internal logic.

Power Architecture: Beyond the Efficiency Horizon

Current power architectures often prioritize peak efficiency at the cost of long-term component health. High-efficiency power supply units (PSUs) frequently use smaller, more stressed capacitors and transistors to achieve their ratings, leading to shorter lifespans. Designing for permanence involves a pivot toward heavy power electronics that prioritize thermal mass and voltage stability over marginal efficiency gains. These robust architectures can absorb grid transients and thermal spikes without degrading the internal circuitry of the compute nodes. By building in significant overhead, architects ensure that the power delivery system remains a permanent fixture of the data center. This strategy reduces the frequency of rip-and-replace upgrades that generate massive amounts of e-waste under circularity frameworks.

In addition to hardware robustness, the logic of power distribution must evolve to support the permanence of the physical plant. Direct-to-chip cooling and high-voltage DC distribution reduce the number of conversion steps, each of which represents a potential failure point. By simplifying the path from the energy source to the processor, engineers minimize the thermal stress on the system as a whole. This simplification is a hallmark of permanent design, as fewer components naturally lead to higher reliability and longer service lives. Operators are discovering that the most sustainable systems are those that avoid the complexity of modern flexible architectures. Permanence, in this context, is achieved through a rigorous commitment to simplicity and the elimination of extraneous features.

The Builder’s Dilemma: Longevity Versus Agility

Builders of modern systems often struggle with the trade-off between the agility of modularity and the stability of permanence. Circularity promises agility by making every part of the system replaceable and potentially recyclable, but this creates a culture of disposability. Permanent design challenges this by asking builders to commit to a long-term vision of the system’s role and capacity. This commitment requires a more sophisticated understanding of future-proofing that does not rely on swapping out parts every few years. Instead, it relies on building systems with enough headroom to remain relevant as computational demands evolve. Architects who embrace permanence find that it forces a more disciplined approach to system design and resource allocation.

The industry must also address the economic incentives that favor the frequent replacement of hardware over the maintenance of permanent assets. Current depreciation models and tax structures often reward companies for refreshing their hardware at a rapid pace. A shift toward permanence would require a re-evaluation of how infrastructure value is measured over decades rather than years. Builders are now looking at historical examples of long-lived infrastructure, such as hydroelectric dams or telecommunications vaults, for inspiration. These structures were built with the expectation of a century of service, a stark contrast to the five-year lifespan of a modern server. Adopting this civil engineering mindset for compute infrastructure is the only way to achieve true sustainability.

Reclaiming the Narrative of Durability

In certain infrastructure contexts, the environmental cost of collecting, transporting, and processing hardware for recycling can materially reduce the net sustainability benefits of material recovery. These impacts vary widely based on geography, logistics efficiency, and processing methods, but they highlight that recycling is not inherently low-impact in all scenarios. Designing systems to remain operational in place for extended lifespans can, in some cases, avoid these downstream logistical burdens altogether.This focus on the micro level of design is what enables the macro goal of long-term infrastructure stability.

Furthermore, the environmental impact of the logistics required for circularity is often underestimated in sustainability reports. The carbon footprint of collecting, transporting, and processing recyclable hardware can outweigh the benefits of the reclaimed materials. Permanent design eliminates these logistical burdens by keeping assets in place and operational for their entire extended lifespan. This static approach to sustainability is far more effective at reducing the total carbon intensity of a system. When a system is permanent, its environmental impact is front-loaded and then amortized over a much longer period, leading to a lower annual footprint. This realization is pushing the world’s largest compute providers to reconsider their commitment to rapid hardware iterations.

The Geopolitics of Material Permanence

The stability of global compute supply chains faces threats from the concentration of mineral refining. Circularity models focus on reclaiming minerals at the end of a hardware lifecycle. However, the energy cost of chemical recycling often offsets the environmental gains. Designing for permanence mitigates this geopolitical risk by reducing total material volume requirements. Operators who invest in ultra-durable hardware effectively stockpile mineral value within their own infrastructure. This strategic restraint ensures that a facility remains operational during prolonged trade disruptions. Consequently, permanence becomes a tool for sovereignty in an era of resource scarcity.

Rivalries between technological powers have accelerated restrictions on advanced components and manufacturing equipment. In this climate, extending the life of existing hardware is more valuable than promised replacements. Permanent design shifts focus from silicon procurement to the preservation of existing capacity through hardening. By over-provisioning cooling, architects create environments where silicon operates for decades without thermal stress. This approach reduces dependency on the fragile logistics networks that define the circular economy. Restraint in replacement cycles is now a critical component of institutional resilience. Long-term infrastructure security requires a departure from the just-in-time procurement mentality.

Operational Excellence through Passive Resilience

Passive resilience represents the pinnacle of permanent design by utilizing physics rather than mechanical systems. By eliminating active cooling components, architects remove the most frequent points of mechanical failure. Thermal mass and natural convection create a self-regulating environment that requires minimal energy input. These passive systems are inherently more durable because they do not rely on moving parts. Frictional wear and fatigue are the primary enemies of longevity in high-scale compute. This shift toward low-tech solutions ensures that core infrastructure survives for decades with negligible maintenance. Builders find that the most resilient systems work in harmony with their physical surroundings.

Implementing passive resilience extends to structural shielding from electromagnetic interference and environmental contaminants. Permanent infrastructure uses hermetically sealed enclosures and advanced insulation materials that do not degrade. These physical constraints prevent the corrosion that typically destroys electronics in modular facilities. By treating the data center as a long-lived asset, engineers justify using superior materials. This architectural permanence provides a stable platform for multiple generations of logic. Even as internal software evolves, the physical housing remains a constant, reliable anchor. Passive resilience transforms the data center from a temporary warehouse into a monument to stability.

A New Economic Framework for Infinite Assets

Current financial models assume rapid obsolescence and aggressive depreciation schedules for technology. Transitioning to permanence requires a fundamental shift in how capital expenditures are amortized. When a system lasts twenty-five years, the annual cost of ownership drops significantly. This economic shift rewards builders who prioritize durability over lower upfront costs. Institutional investors recognize that permanent infrastructure provides a predictable return in a volatile economy. As a result, the infinity asset model is emerging as a preferred strategy. Funding the next generation of compute requires a commitment to these long-term valuation cycles.

Tax codes and accounting standards must evolve to distinguish between disposable and permanent infrastructure. Current policies often penalize maintenance while incentivizing the acquisition of new, less durable hardware. Permanent design thrives in environments that value resource preservation over constant recycling loops. Builders and architects must advocate for changes that align financial incentives with physical reality. By lengthening the investment horizon, the industry can move away from frantic refresh cycles. This financial restraint is the necessary foundation for building infrastructure that stands the test of time. Sustainable growth requires a move toward assets that do not require constant capital injections.

The Future of Permanent Infrastructure

The future of high-scale compute will involve a bifurcation between edge devices and permanent core infrastructure. The core will feature massive, hardened structures serving as the bedrock of the digital economy. These facilities will utilize power architectures integrated into the very fabric of the building. Such integration makes the infrastructure impossible to recycle but incredibly durable over time. Designing for permanence allows for a predictable energy profile for the entire grid. As the world moves toward electrification, stable compute hubs will balance intermittent renewable sources. These facilities will act as thermal and electrical anchors for the surrounding urban environment.

The shift toward permanence represents a maturing of the technology industry’s relationship with the physical world. We cannot simply recycle our way out of massive material requirements for modern civilization. By building for the long term, we respect the scarcity of materials and energy. Restraint, durability, and longevity must become the new metrics of success for system architects. The world’s most sustainable systems will not be those that are best at being rebuilt. Instead, the most successful systems will be those that never need a replacement. This is the essence of designing for permanence in an age of scarcity.