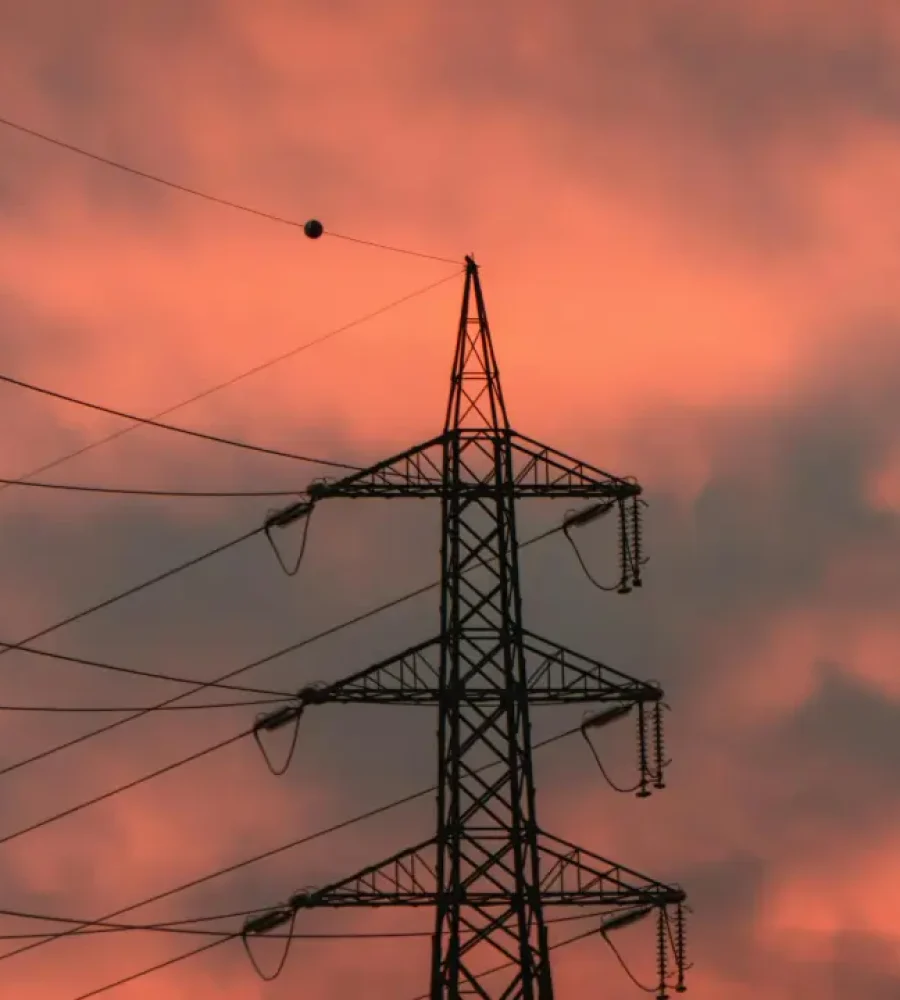

Across the United States and Europe, utilities report massive backlogs of interconnection requests that far exceed available capacity. As a result, project timelines and regional economic plans face growing risk. Traditional power grids in major technology markets struggle to keep pace with the surge in electricity demand driven by AI and hyperscale data centers, pushing interest toward grid-independent data center architectures. In Texas alone, interconnection requests from data center developers have climbed into the hundreds of gigawatts. This surge has overwhelmed transmission systems and forced grid operators into emergency planning.

As grid congestion worsens, energy strategy has shifted from a secondary planning concern into a core constraint on AI growth. Delays of four to seven years for grid connections are now common. These delays far exceed the typical construction timeline for a data center. Companies increasingly face a hard reality. They cannot scale compute on hardware schedules if they depend on slow and uncertain grid upgrades. In response, the industry is rethinking how data centers are powered. More operators now explore grid-independent architectures that rely on on-site generation rather than waiting for utility delivery.

This shift has given rise to what some analysts describe as the Sovereign Data Center. The model centers on energy independence and combines advanced nuclear technologies for baseload power with hydrogen systems for backup and flexibility. Rather than reflecting ideology, it responds to practical constraints. Control over energy supply may soon become as strategic as control over compute itself.

Why Sovereignty Matters

AI and machine learning workloads are rewriting the electricity playbook. Modern AI data centers consume far more power than earlier generations of facilities. Deloitte estimates that U.S. AI data center demand could grow more than thirtyfold by 2035. Demand would rise from roughly 4 gigawatts in 2024 to over 120 gigawatts. That level rivals the electricity needs of entire metropolitan regions. It also arrives on top of broader electrification trends that already strain existing grids.

In response, governments and utilities have introduced new planning frameworks, demand forecasting tools, and grid modernization efforts. For example, PJM Interconnection in the Mid-Atlantic has proposed mechanisms that require large power customers to supply part of their own energy. Alternatively, customers may accept curtailment during emergencies. These measures, however, function largely as stopgaps. When demand growth outpaces transmission expansion, the most scalable solution brings generation closer to the load. Waiting for upgrades often takes too long.

For many operators, on-site generation is no longer optional. The logic has become straightforward. If the grid cannot deliver power on a timeline that aligns with hardware deployment and cost expectations, facilities must secure their own firm supply. In this context, sovereignty means controlling when and how compute scales. Operators no longer remain constrained by external network congestion.

The Nuclear Pillar of Sovereignty

At the core of the sovereign data center model lies nuclear energy, particularly Small Modular Reactors. These next-generation reactors are designed for factory production and scalable deployment. Compared with traditional gigawatt-scale plants, SMRs require smaller footprints. Developers can also site them closer to end uses such as data centers.

SMRs address one of the most critical challenges for AI infrastructure. Data centers require continuous, firm power. Intermittent renewable sources cannot reliably meet this requirement on their own. Even brief outages or voltage fluctuations can disrupt workloads and generate significant financial losses. Nuclear power provides steady baseload generation with minimal carbon emissions. This reliability makes it well suited for high-demand computing environments.

Around the world, utilities and technology companies are already exploring nuclear arrangements tailored to data center loads. In the United States, Google has signed a power purchase agreement tied to the Hermes 2 advanced nuclear reactor. This deal signals how firms are securing clean, firm power for future facilities.

Critics note that SMRs have not yet reached mass production. Commercial deployment timelines also extend into the late 2020s or early 2030s. Even so, growing interest in nuclear integration reflects rising urgency. Operators want reliable power outside the traditional grid. SMRs represent a strategic move away from utility dependence and toward self-contained infrastructure aligned with AI growth schedules.

Hydrogen: Flexibility and Backup

While nuclear power provides a stable foundation, modern data centers also require flexibility. Facilities must accommodate load fluctuations, peak demand, and emergency scenarios. Hydrogen plays a complementary role in meeting these needs.

Green hydrogen is produced through electrolysis powered by excess nuclear or renewable generation. It can function as both energy storage and backup power. Unlike diesel generators, hydrogen fuel cells generate electricity without nitrogen oxides or carbon dioxide emissions. This advantage matters as environmental standards tighten. Hydrogen-based backup systems also align with corporate sustainability goals and emerging regulatory frameworks.

Hydrogen systems can often deploy faster than large thermal plants. Companies developing hydrogen fuel cell solutions now position them as modular, on-site power assets. These systems pair naturally with nuclear baseload generation. This modularity enhances resilience. Facilities can remain operational during grid disruptions, maintenance outages, or extreme weather events.

By combining nuclear baseload with hydrogen storage and backup, sovereign data centers address both continuous demand and short-term peaks. Together, these systems improve reliability. They also reduce exposure to external fuel supply chains and grid curtailments.

What Sovereignty Really Means

In practice, sovereignty encompasses three distinct but related dimensions.

Energy sovereignty refers to full control over power supply without reliance on congested transmission systems. This control protects operators from blackouts, price volatility, and regulatory delays that can stall expansion.

Operational sovereignty involves decoupling compute deployment from utility permitting cycles. When power is generated on site, timelines depend on construction and logistics. They no longer hinge on interconnection studies that can stretch for years.

Data sovereignty reflects the security benefits of electrically isolated facilities. Sites that generate their own power face less exposure to cascading failures on public networks. They also maintain stronger physical and operational resilience.

Together, these dimensions describe an integrated model. Compute, energy, and operational control converge within a single strategic asset.

Comparing Traditional and Sovereign Architectures

Traditional data centers rely on utility grids for primary power and diesel generators for backup. This approach worked historically, but it has grown increasingly fragile. Demand continues to accelerate, renewable integration increases, and infrastructure ages. Sovereign data centers take a different approach. They replace grid dependence with on-site nuclear baseload and hydrogen-based flexibility. This shift shortens deployment timelines and stabilizes long-term costs.

In conventional projects, interconnection delays and grid upgrade requirements often inflate budgets. These delays also postpone commissioning. Sovereign designs largely avoid these bottlenecks. They deliver capacity more predictably while aligning energy supply with sustainability objectives.

This architecture also creates opportunities for heat reuse and local value creation. Waste heat from generation can support industrial processes or district energy systems. These uses improve overall efficiency.

An Emerging Infrastructure Era

AI-driven demand is forcing a fundamental reassessment of energy planning. Existing grids were not designed for the scale or speed of modern compute growth. The sovereign data center model responds by reimagining how energy and compute infrastructure integrate.

By pairing advanced nuclear power with hydrogen-based flexibility, operators can anchor AI expansion in reliable, low-carbon, and independent energy systems. These facilities do not withdraw from the grid. Instead, they respond strategically to its structural limits. Over the next decade, the ability to generate and manage power on site may become as essential as compute density or cooling performance.

Sovereign data centers will not replace grids entirely. Still, they represent a new frontier in how energy and compute co-evolve in the AI era.