“We were told that the internet erases identity, but the opposite is true.”

MIT’s Joy Buolamwini warned us of this.

For decades, technology promised neutrality: data would be fair, algorithms unbiased, and AI corrective of human inequities. That promise is now unraveling.

AI shapes hiring, healthcare, credit, and policing. It absorbs societal biases instead of erasing them. Training data reflects historical discrimination, gender inequality, and economic exclusion. Entire populations, especially in the Global South, remain underrepresented. Algorithms trained on these distortions do not fix them; they amplify them.

The consequences are real. Facial recognition misidentifies darker-skinned faces. Hiring tools disadvantage women. Healthcare models misdiagnose non-Western patients. Credit systems quietly exclude marginalized communities. The danger grows because algorithmic decisions appear neutral and often remain invisible.

Global AI development concentrates in a few countries, but its impact spreads worldwide. Models trained on limited datasets embed biases across borders, reinforcing inequality and risking new forms of digital colonialism.

How Training Data Becomes Biased

AI learns patterns from the data we provide. But all data reflects a slice of the world, filtered through human institutions, histories, and blind spots. When that slice is unbalanced, AI misinterprets reality. Historical records often favor the status quo: many government and corporate datasets over-represent dominant groups while excluding marginalized populations. One analysis notes that AI models “replicate racist and gender-related bias in society,” reinforcing historical discrimination. Workplaces dominated by men produce employee databases filled mostly with men. Tech hiring networks continue past biases. Social media content favors certain languages and cultural norms. AI trained on these skewed samples absorbs the wrong lessons.

Bias also enters through data gaps. The Brookings Institution calls this “algorithmic exclusion.” Even when data lacks overt prejudice, “fragmented, outdated, low-quality, or missing” data harms people by making them invisible to AI. Poor internet access, limited digital infrastructure, and fewer interactions with data-collecting institutions leave entire communities without a digital footprint. AI trained on global data can simply ignore these “data deserts.” As Catherine Tucker notes, “the absence of data…can be just as harmful as the inclusion of overtly biased data.” If an AI has never “seen” people from certain regions, it cannot handle their cases accurately. This issue is particularly urgent in the Global South, where billions remain underrepresented in international datasets.

Beyond quantity, the type of data collected and how it is labeled matters. Many AI models simplify complex realities into rigid categories (e.g., male/female, hire/fire, credit/no credit). Underrepresented identities get pushed to the margins or erased entirely. Machine learning often classifies gender in binary terms, leaving non-binary and transgender people invisible to technology. Facial recognition systems trained on mostly light-skinned faces perform poorly on darker-skinned individuals, as MIT’s Gender Shades study showed. The cause is simple: if the training set contains mostly one type of face, the algorithm treats that as the norm. Buolamwini found that commercial face-recognition software misidentified dark-skinned women’s gender 35% of the time, while it performed nearly perfectly on light-skinned men. She summarized in a TED talk: “If the training sets aren’t really that diverse, any face that deviates too much from the established norm will be harder to detect.”

Data selection also introduces bias through convenience or ideology. Tech companies often scrape the internet indiscriminately, which amplifies existing biases. Gebru et al. note that as firms rush to build ever-larger models, “white supremacist and misogynistic, ageist, etc.” content on the web enters the training corpus, giving undue weight to extremist viewpoints. Many language and image models also rely on English and Western sources, absorbing Western cultural assumptions while missing nuances from other regions. Algorithmic bias is rarely a coding flaw; it comes from the data itself. As one expert put it: “If you train an AI on biased data, it will give you biased results.”

Healthcare: Misdiagnosis and Exclusion

In medicine, biased data can literally cost lives. Many health-focused AI tools train on patient data from wealthy, developed countries, usually in the Global North. The World Economic Forum notes that most AI health systems use “data from high-income countries, leaving billions of people in the Global South invisible in diagnostic models.” Tools tested and tuned in Western hospitals often fail when used in Africa, South Asia, or Latin America. Without representative data, AI-driven diagnostics and risk assessments misdiagnose or entirely miss conditions in underrepresented populations.

For example, 80% of genomic research involves people of European descent. Genetic risk calculators and personalized medicine models work best for these populations. Tools that detect diseases often assume skin, bone structure, or symptom presentations based on those mostly studied groups. A striking case involves AI algorithms for skin cancer detection. Models trained on lighter-skin images perform poorly on dark skin. A tumor flagged as suspicious on a white arm might go unnoticed on a Black arm by the same algorithm. In cardiac care, risk calculators developed on European or American cohorts may over- or underestimate heart disease risk for African, South Asian, or Latino patients.

The consequences are grave. AI that consistently overlooks disease in non-Western patients causes misdiagnoses and delays treatment, worsening health inequities. Patients may receive inappropriate medications or, worse, face life-threatening conditions ignored entirely.

To earn trust and deliver benefits worldwide, AI in healthcare must reflect global diversity. Efforts exist; for example, Rwanda’s Digital Health Initiative collects African medical data to fill these gaps, but we need much more inclusive data curation to prevent AI from deepening, rather than healing, inequalities.

Hiring and Workplace Decisions

Algorithms increasingly screen candidates, assess employees, and guide promotions. Unfortunately, these tools often codify past hiring biases. A landmark example came from Amazon in 2018. The company trained a resume-screening AI on a decade of applications, most from men. The AI learned to favor male-dominated resumes and penalized applications containing the word “women’s,” as in “women’s chess club captain.” In practice, the system concluded that “male candidates were preferable” and downgraded profiles associated with women. Amazon eventually scrapped the project but not before the case became a cautionary tale. As Reuters reported, the AI “taught itself” these preferences from the imbalanced data.

The root problem lies in training data. If an organization historically employed few female or minority executives, an AI recruiter concludes that pattern is “successful” and reinforces it. Similar issues appear with algorithms trained on salary histories, performance reviews, or promotion records containing discrimination. For example, a company that historically promoted mostly straight people may unintentionally train an AI to rate same-sex or unmarried profiles lower, a phenomenon observed in a U.S. municipal hiring AI years ago. Under such systems, qualified candidates lose opportunities due to irrelevant factors.

These biases appear throughout HR. Credit Suisse once used an algorithm to rate job candidates and inadvertently downgraded female applicants. LinkedIn job recommendations often show high-paying roles mainly to men, highlighting pay gaps. Even simple cues, such as “professional” appearance, can encode bias. An educator exercise cited by Edutopia showed that Google Image’s search for “professional hairstyle” mostly displayed straight, light-colored hair. The authors concluded: “If an algorithm used for hiring is trained on datasets that equate ‘professionalism’ with certain hairstyles, you’ve built a biased system right from the start.” Technology mirrors society’s hiring prejudices.

Impact on Workers

Biased hiring algorithms block entire groups from opportunities. Women may see roles automatically filtered out. Minority candidates face fewer callbacks or stricter AI screening. These systems perpetuate income and status disparities. At a systemic level, bias entrenches segregation and slows diversity efforts. Researchers warn that biased workplace AI “replicate historical human biases,” meaning the glass ceiling becomes hard-coded.

Jobs and income determine individual and family livelihoods. AI hiring biases have ripple effects. For individuals, being unfairly rejected or downgraded by an algorithm feels opaque and unjust; applicants rarely know why they were turned down. At the societal level, entire demographics remain locked out of economic mobility. One analyst explains that in tech’s drive for efficiency, the “people who have been systematically underrepresented or evaluated to their disadvantage” offline risk being “enveloped and trapped in emerging AI apartheid systems.” We could see two labor markets emerge: one for “data humans” whose profiles match training data, and another for everyone else.

Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice

The most urgent and controversial application of biased AI appears in policing and courts. Police departments deploy facial recognition cameras, and courts rely on risk-assessment tools for bail or sentencing. When these systems draw on biased data, the results can be catastrophic.

One notorious example involves the COMPAS risk-assessment algorithm in U.S. courts. A ProPublica investigation found that COMPAS falsely flagged nonviolent Black defendants as high-risk almost twice as often as white defendants (45% vs 23%). In other words, a Black defendant who would not reoffend had nearly double the chance of being labeled “high risk” compared to a white nonviolent defendant. This outcome stemmed from the algorithm’s training on historical crime data that reflected systemic over-policing of Black communities. Timnit Gebru noted: “When an AI system is trained on historical data that reflects inequalities … it is not only often wrong, but also dangerously biased.” The consequence: more Black people faced bail denials or harsher sentences than their behavior justified, perpetuating racial disparities.

Facial recognition poses another flashpoint. Multiple studies and real-world incidents show these systems struggle with non-white faces. A U.S. government NIST report found that African American and Asian faces were misidentified 10 to 100 times more often than Caucasian faces in “one-to-one” searches. African-American women experienced especially high error rates in “one-to-many” searches. In practice, police cameras misidentify innocent people of color much more often. A striking Reuters example: in Brazil, police facial-recognition software labeled American actor Michael B. Jordan as a Brazilian crime suspect because it failed to distinguish Black faces correctly. Such errors have real consequences: wrongful arrests, invasions of privacy, and erosion of civil liberties.

Public outcry highlights the stakes. During U.S. protests in 2020, calls grew to ban “racially biased surveillance technology.” Tech policy experts warn that most facial recognition algorithms rely on photos that “often underrepresent minorities” and therefore “struggle to recognize ethnic minority faces.” Civil society groups also note that misleading video algorithms can fuel false arrests and harassment. For example, an ACLU study found Amazon’s Rekognition system incorrectly matched 28 of 535 Congress members’ photos, disproportionately misidentifying Black lawmakers as criminals. The lesson is clear: training data that lacks diversity or carries prejudice can “supercharge” historic injustices in policing.

Globally, similar patterns appear. In Brazil, where over half the population is Black or mixed-race, experts point to “algorithmic racism.” Developers from outside Brazil sometimes assume a race-blind society, unintentionally embedding bias in systems. Black Brazilians might get lower credit scores or face flawed law enforcement AI, reinforcing poverty and police violence. In the UK and U.S., Black and Indigenous communities dominate criminal justice datasets, so risk models trained on that data disproportionately flag them.

Finance and Lending

Financial institutions increasingly rely on algorithms for credit scoring, loan approvals, and insurance underwriting. Yet when training data reflects historical redlining or bias, algorithms replicate those patterns. A major investigation by The Markup (using U.S. mortgage data) found clear racial bias in lending approval rates. Black applicants, even those earning $100,000 a year with low debt-to-income ratios, received loan denials more often than white applicants with higher debt. High-earning Black applicants with little debt still faced worse odds than similarly qualified white applicants. The Markup summarized: “Lenders used to tell us… the ethno-racial differences would go away if you had [credit scores]; Your work shows that’s not true.” Even at identical credit scores, Black, Latino, and Asian applicants were up to 120% more likely to be denied than whites.

Credit algorithms learn from historical lending data. If that history involves redlining, refusing loans to minority neighborhoods, AI treats those patterns as rules. Financial models may find “non-White” or certain ZIP codes correlate with defaults, labeling them high-risk regardless of an individual’s actual finances. Insurance and hiring algorithms show similar patterns. Online job listings may target or hide opportunities based on gender or race, guided by biased user data.

Impact: Biased finance algorithms widen economic gaps. Denying loans to minority entrepreneurs or home buyers perpetuates wealth disparities. People struggle to build businesses or secure stable housing, reinforcing poverty cycles. At a societal level, these systems lock racial wealth gaps into “algorithmic law”: decisions that were once illegally prejudiced now hide behind technical determinism. Victims rarely know why an algorithm denied a loan, deepening mistrust in banks and technology.

Because financial power amplifies opportunity, biased algorithms can cement global inequality. If multinational credit databases and fintech models rely mostly on Global North (predominantly white) data, emerging markets and communities of color may face worse credit access. Reuters also found that financial “data deserts” outside the sampled population end up financially marginalized.

Education and Algorithmic Assessment

Educational AI promises personalized learning and automated grading, but it can also reproduce inequality. A stark example came in 2020 with the UK’s exam grading algorithm. To replace canceled A-level results, the government used an algorithm that adjusted students’ grades. The system relied heavily on school-level historical performance, punishing students from underperforming schools. Predictably, students in poorer or rural areas, often ethnic minorities or lower-income, had their grades unfairly downgraded. Students at historically elite schools performed better than expected. When this bias became public, the government abandoned the algorithm.

This incident shows how “neutral” machine learning can perpetuate privilege. The training data, past school results, contained systemic class and regional biases. Studies of educational algorithms confirm that institutional data, such as school records, often contributes most to discriminatory outcomes in student assessment.

Cultural and Linguistic Biases in Education

Outside testing scandals, educational technologies often favor the majority culture. Language and dialect illustrate this clearly. Adaptive learning platforms built on English-only data struggle to teach children who speak other languages. AI reading programs may misinterpret non-standard accents or dialects. An Edutopia analysis warns that AI often “mirrors our prejudices and societal biases.”

Bias also appears in visual and professional cues. One example involved an algorithm trained on office images, equating “professional appearance” with straight, blonde hairstyles. The system automatically labeled Black students with natural hair as “unprofessional,” even before humans reviewed their work. Similarly, AI trained in systems that historically promoted men to leadership is likely to recommend men as leaders again.

Consequences for Students

Biased educational AI can mis-evaluate students and lower expectations for marginalized groups. Adaptive tutors may suggest lower achievement paths for girls or students of color, limiting opportunities to excel. Algorithmic surveillance in classrooms can disproportionately flag students; for example, Black boys may be labeled “trouble” more frequently. Systemically, such AI replicates achievement gaps. Critics warn that “AI has the potential to amplify the bias that exists in our human psyche,” cementing discriminatory norms. The key problem is feeding AI incomplete or unrepresentative educational data.

The Global North-South Divide in AI Data

A major dimension of AI bias is geographic. Most cutting-edge AI trains on data from the Global North, high-income countries like the U.S., Europe, and China, while populations in Asia (outside China), Africa, and Latin America remain underrepresented. This “data colonialism” causes AI systems to fail in the Global South or reinforce marginalization.

For example, a 2025 study on misinformation found that most commercial fake news detection tools trained on Global North content performed poorly on Indian regional-language deepfakes or African social media. One model had a 40% higher false-negative rate on Global South news compared to the North.

Real-World Impacts of Data Gaps

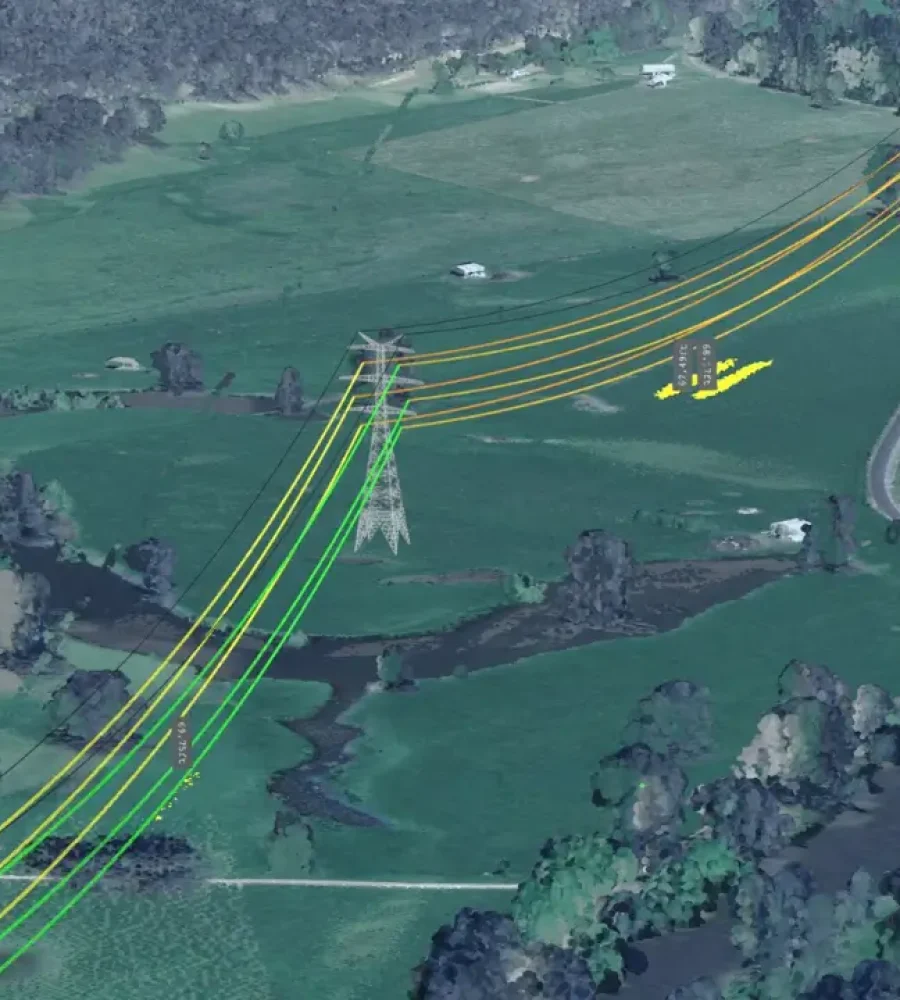

The pattern repeats across sectors. The World Economic Forum reports that nearly 5 billion people live in countries missing from AI healthcare datasets. Most AI image systems primarily see white or East Asian faces, underperforming on Indian, African, or Latin American faces. Voice assistants like Siri or Alexa recognize only a dozen major accents and languages, leaving dozens of African and South Asian languages invisible. Autonomous vehicles and surveillance systems, tested mainly in Western traffic conditions, may fail in other geographies.

This results in digital inequality. AI benefits concentrate in the North. African or Asian farmers gain little from crop disease models trained on U.S. datasets. AI-driven criminal justice reform in the U.S. offers limited utility if local communities aren’t represented. Nieman Lab notes that North-trained models have “very limited utility” for the Global South.

Human Rights and the Need for Inclusive AI

Data gaps carry human rights implications. OpenGlobalRights warns that tech companies rarely engage stakeholders from the Global South, leading to systemic bias in AI models. They describe this as data colonialism: wealthy countries exploit global data while poorer regions remain excluded or misrepresented. For instance, predictive policing systems built on urban crime data may be meaningless in informal settlements, locking systemic discrimination into AI decisions.

Bridging this divide requires deliberate action: building local datasets, translating models, and including Global South voices in AI development. Some initiatives, such as UNESCO’s efforts in fair data governance, are underway, but the imbalance persists. Without change, AI will continue to mirror the narrow realities of its creators, ignoring billions of lives.

Consequences of Biased AI: From Individuals to Societies

Biased AI affects multiple levels of society. For individuals, it can mean lost opportunities, misjudgments, or even life-threatening errors, often without accountability. A person may be refused a job, misdiagnosed in a hospital, denied credit, or wrongly arrested, all by an “invisible” algorithm. These decisions often feel arbitrary because users cannot see how the AI reached them. This erodes trust in both technology and institutions: when people feel discriminated against by a black box, they lose confidence in the systems that govern their lives.

At a systemic level, biased AI solidifies inequality. Communities already facing poverty, racism, or marginalization experience further penalties from automated systems. For example, emergency services using predictive algorithms trained on biased data may under-serve neighborhoods with large minority populations, reinforcing disadvantage. Educational AI that underestimates giftedness in students from certain backgrounds blocks them from academic success at scale. Over time, these individual injustices aggregate into statistical oppression: entire groups are labeled “high risk” or “less deserving,” and society advances along that skewed blueprint.

Globally, biased AI can take the form of digital colonialism. Brookings’ concept of “algorithmic exclusion” highlights how marginalized people become invisible to AI, “systematic under-recognition of the very populations that an equity-focused policy would protect.” As a result, AI tools may benefit wealthy nations while ignoring or harming the rest. Cambridge researchers warn that algorithmic bias produces “cascading negative effects on affected individuals,” particularly in the Global South, making vulnerable populations even more at risk.

Politically, bias erodes democracy and rights. Social media algorithms often amplify certain viewpoints, usually from the Global North, while silencing minority or Southern voices. Surveillance and policing bias fuel social unrest and distrust in governments. Economic bias limits entrepreneurship and education in entire regions. Fundamentally, AI trained on unequal data risks freezing global inequities into code.

Addressing bias is not just a technical challenge, it is a matter of social justice. The question shifts from “Can AI be fair?” to “Who benefits from AI, and who suffers?” One analyst notes: “The problem with AI is not only the ingrained biases in individual programs, but also the power dynamics that underpin the entire tech sector.” Technologies designed by and for the powerful risk perpetuating oppression rather than enabling progress.

Mitigating Bias: Toward Fairer, More Inclusive AI

Researchers, companies, and governments are exploring solutions on multiple fronts. A key theme is inclusive data and AI development. This includes curating datasets that better represent diverse populations. In healthcare, projects in Africa, Asia, and Latin America now collect local health data for AI training, realizing that “representative data is the core of inclusive AI.” International cooperation supports these efforts: initiatives like the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health show how medical data can be shared across borders to improve AI models. In finance, regulators push for more complete data collection, following examples like The Markup investigation, to prevent hidden discrimination.

Policy and oversight provide another defense. Many jurisdictions now regulate AI to demand fairness. The EU’s AI Act will categorize high-risk AI, including credit scoring and employment screening, requiring audits and bias mitigation. In the U.S., the Algorithmic Accountability Act (reintroduced in 2023) directs the FTC to enforce AI impact assessments. Some cities, including San Francisco, have banned or limited facial recognition in law enforcement. Standards bodies like NIST have published AI risk frameworks, and major platforms now allow research access or documentation of model training data. Proposals for “geopolitical model cards” aim to disclose Global North–South biases.

On the technical side, debiasing methods exist. Teams apply fairness algorithms, reweighting datasets or removing sensitive features, during training. Tools like IBM’s AI Fairness 360 detect bias in models. Experts caution that these solutions are stopgaps: audit-centric approaches risk reducing bias to a checkbox without addressing societal inequalities. Catherine Tucker emphasizes that even perfectly unbiased models cannot overcome missing data, also known as algorithmic exclusion. Still, technical fairness measures can reduce egregious errors, for instance, adjusting hiring AI so female-coded resumes are not unfairly downgraded, if we know what to fix.

Community Engagement and Inclusive Practices

Many experts stress community involvement. Grassroots and civil-society initiatives, such as the Algorithmic Justice League co-founded by Joy Buolamwini, push for transparency and equitable design. Educating developers to recognize bias, involving domain experts (e.g., anthropologists, ethicists), and including voices of affected groups can transform AI workflows. Community-driven data collection, crowdsourcing local images, texts, or voice samples, builds more representative training sets. Some propose “AI cooperatives,” where communities own data and models about them. In hiring and education, teachers and recruiters are encouraged to provide qualitative feedback rather than treat AI output as unchallengeable.

The Moral Imperative

Biased training data perpetuates and worsens global inequalities across healthcare, employment, justice, finance, and education. Harms range from personal injustices, wrongful arrests, misdiagnoses, denied jobs or loans, to systemic oppression, deepening racial and international wealth gaps. Experts recommend diverse datasets, transparency through model cards, algorithmic audits, inclusive AI development, and strong policy interventions. Ensuring that AI serves all people, especially historically marginalized groups, is above all, a moral imperative.