The global expansion of digital infrastructure is now colliding with physical limits. Land scarcity is intensifying. Power grids are reaching saturation. Freshwater supplies are under pressure. At the same time, generative artificial intelligence and large language models continue to drive unprecedented computing demand.

As a result, the data center industry must rethink how it builds and operates facilities. Traditional land-based data centers consume vast resources. Mid-sized facilities use as much water as a small town. Larger hyperscale campuses can require up to five million gallons of water per day. Consequently, industry leaders are searching for structural alternatives for cooling AI.

In this context, underwater data centers have moved beyond theory. They now represent a serious strategic frontier.

Why Underwater Data Centers Matter Now

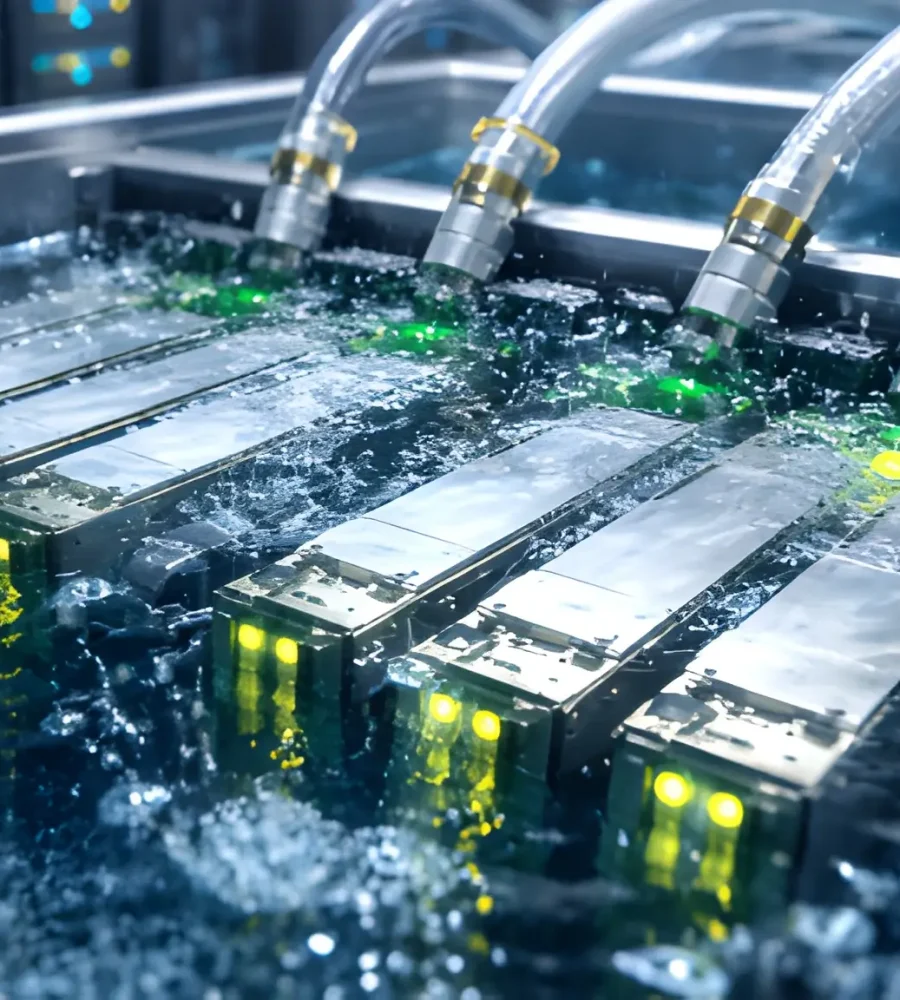

Underwater data centers, or UDCs, signal a fundamental shift in how the digital economy manages cooling and energy use. Instead of relying on evaporative systems and mechanical chillers, operators use the ocean’s natural thermal stability. This approach significantly reduces energy devoted to cooling.

Cooling systems typically account for up to 40 percent of total facility energy use in traditional data centers. However, underwater systems aim to cut that share dramatically. Therefore, UDCs offer both performance and sustainability advantages.

This report examines global underwater data center initiatives. It compares Western research-led experiments with Asia’s commercial scale-up efforts. In addition, it evaluates the engineering, economic, and regulatory factors that determine long-term viability in subsea environments.

The Terrestrial Resource Crisis and the Subsea Imperative

The push toward underwater data centers stems from the unsustainable trajectory of land-based computing.

In the United States alone, data centers consumed approximately 176 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2023. That figure rivals the total national energy consumption of Ireland. Moreover, analysts expect demand to double or even triple by 2028. As a result, already stressed power grids face mounting strain.

Water usage has also drawn intense scrutiny. Evaporative cooling systems consume massive quantities of freshwater. A single AI training session can use hundreds of thousands of liters of water. Even routine chatbot interactions carry hidden water costs. Every 20 to 50 queries can indirectly consume about half a liter of water.

Public opposition has grown in response. Regulators have increased oversight. In water-stressed regions such as Arizona, Nevada, and Northern Virginia, communities have challenged new data center developments. Critics often describe the phenomenon as a “giant soda straw” effect, where facilities draw heavily from local aquifers and reservoirs.

Underwater data centers directly address this tension. Operators use seawater as a cooling medium. They do not withdraw freshwater from municipal supplies. Consequently, UDCs eliminate one of the most controversial aspects of terrestrial infrastructure.

Furthermore, nearly half of the world’s population lives near coastlines. By deploying compute capacity offshore, operators can position facilities closer to end users. This proximity can reduce latency for edge applications by as much as 98 percent. Therefore, the subsea model improves both sustainability and performance.

Comparative Resource Metrics: Terrestrial vs. Underwater Data Centers

Below is a simplified comparison of key operational metrics:

Cooling Energy Consumption

Land-based centers: 30 to 40 percent of total facility power

Underwater centers: Less than 10 percent

Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE)

Land-based: 1.8 to 4.8 liters per kWh

Underwater: Zero freshwater withdrawal

Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE)

Land-based: 1.5 to 2.0 standard, 1.1 best-in-class

Underwater: 1.01 to 1.15

Maintenance Failure Rate

Land-based baseline: 1.0

Underwater: 0.125, or one-eighth of baseline

Land Use Footprint

Land-based: Hundreds of acres

Underwater: Minimal seabed or near-shore placement

Taken together, these metrics explain why the subsea model has gained strategic attention.

The Architectural Legacy of Microsoft Project Natick

Modern underwater computing began with Microsoft Project Natick. The initiative evolved from a 2013 internal white paper into a series of real-world maritime deployments.

Sean James, a former Navy submariner, played a key role in shaping the concept. He applied naval engineering principles to server infrastructure design. As a result, the team treated the data center as a sealed, pressure-managed vessel rather than a conventional building.

Phase 1: The Leona Philpot Prototype

Microsoft launched Phase 1 in 2015. The company deployed a 38,000-pound cylindrical container off the California coast. The team named it “Leona Philpot.”

The 105-day mission tested a fundamental question. Could a sealed vessel dissipate the heat generated by roughly 300 desktop-class PCs without overheating or structural failure?

The results were clear. The ocean effectively absorbed the thermal load. The internal systems remained stable. Therefore, Microsoft confirmed that subsea cooling worked in calm, shallow waters.

This proof of concept provided the data needed for a more ambitious deployment.

Phase 2: Hyperscale Validation in the Northern Isles

In 2018, Microsoft deployed the “Northern Isles” vessel off the Orkney Islands in Scotland. The company collaborated with Naval Group to manage the engineering process. This deployment represented a major leap in complexity.

The pod measured roughly the size of a 40-foot shipping container. Engineers submerged it 117 feet below the surface in the turbulent waters of the North Sea.

Northern Isles Technical Profile

Payload

12 racks

864 servers

27.6 petabytes of storage

Cooling System

Passive heat exchangers with a seawater loop

Internal Atmosphere

One atmosphere of dry nitrogen with no oxygen

Operational Duration

25 months from 2018 to 2020

Reliability Performance

Eight times fewer failures compared to land-based control group

Power Source

100 percent locally produced renewable energy

The Northern Isles mission produced a landmark reliability result. The server failure rate measured one-eighth of comparable terrestrial facilities.

Microsoft attributed this improvement to two primary factors. First, engineers removed oxygen from the internal environment. This eliminated oxidative corrosion. Second, the sealed system eliminated human interference.

In traditional data centers, technicians frequently replace components. That activity introduces dust, humidity fluctuations, and mechanical disturbance. By contrast, the Natick pod maintained a stable, pristine environment. Consequently, standard commodity hardware operated longer and more reliably.

The Logistics of Success and the Paradox of Scale

While Project Natick was a resounding technical success, it was officially discontinued in 2024. The “what didn’t work” aspect of Natick was not the engineering, but the commercial logistics of the sealed-vessel model. Microsoft’s current cloud strategy prioritizes the rapid, dynamic scaling of AI infrastructure, where hardware is often refreshed or upgraded every 12 to 18 months. The Natick model—designed for 5-year “lights out” cycles without human access—was fundamentally incompatible with this need for agility.

The “retrieval tax” became the project’s primary economic barrier. Surfacing a 40-foot vessel from the seafloor requires specialized heavy-lift ships and favorable weather windows, with costs often exceeding $1 million per operation. For a company focused on hyperscale expansion, the inability to easily swap a failed GPU or upgrade a network switch meant that the subsea pod was essentially a “black box” that could not keep pace with the volatile hardware requirements of generative AI. Consequently, Microsoft transitioned its focus toward applying Natick’s learnings, specifically nitrogen-sealing and advanced liquid cooling, to terrestrial and edge facilities.

China’s Commercial Pivot: The Integrated Maritime Cloud

If Microsoft proved the science, China has formalized the industry. By integrating UDCs into its “Blue Economy” strategy, China has moved beyond research to create operational computing clusters in Hainan and Shanghai. This approach is characterized by government-backed consortiums, massive capital investment, and a strategic focus on supporting the nation’s AI and 5G ambitions.

The Hainan Underwater Intelligent Computing Cluster

In late 2023, the world’s first commercial underwater data center was activated off the coast of Lingshui, Hainan Island. This project, a collaboration between Beijing Highlander, Shenzhen HiCloud, and local state-owned assets, represents a transition to mid-scale commercial deployment. The facility operates at a depth of 115 feet and is designed to handle a variety of intensive workloads, including AI model training using the DeepSeek framework.

Hainan UDC Commercial Performance Indicators

- Compute Power: Equivalent to approximately 30,000 high-end gaming computers

- Server Density: 24 racks, approximately 500 servers per cabin

- Operational Goal: 100 cabins in a networked grid

- Energy Efficiency: 40-60% better than comparable land-based sites

The Hainan project addresses the “scale” problem that Natick faced by planning for a network of 100 interconnected cabins rather than a single isolated vessel. This modular grid allows for redundancy; if one cabin fails or requires maintenance, the workload can be dynamically shifted to others in the cluster, effectively treating the seafloor as a distributed data hall.

The Shanghai Wind-Powered Benchmark

In October 2025, China reached a new milestone with the completion of the world’s first wind-powered UDC off the coast of Shanghai. This project, situated in the Lin-gang Special Area, integrates 95% to 97% offshore wind energy directly into the computing load. This co-location strategy is a masterstroke of resource efficiency: it uses the ocean to cool the servers while using the offshore wind turbines to power them, eliminating the energy losses associated with long-distance transmission from terrestrial grids.

The Shanghai facility has achieved a PUE of 1.15, well below the national mandate of 1.25 for new large-scale data centers. By spending approximately $226 million on the first phase, China has demonstrated that UDCs can be financially viable when treated as an infrastructure-scale investment rather than a research experiment. The facility is not merely for data storage; it is specifically engineered to power AI workloads, 5G industrial IoT, and international data flows, positioning it as a green “high-performance computing cluster”.

Engineering Divergence: The Physics of Containment

The technical evolution of underwater data centers has led to two distinct architectural philosophies: the sealed pressure vessel and the pressure-equalized chamber. These designs represent different approaches to the fundamental physics of the deep-sea environment, specifically the management of hydrostatic pressure and heat flux.

Sealed Pressure Vessels: The Traditional Hull

Used by Project Natick and the Hainan UDC, this model relies on the structural integrity of the vessel to maintain a terrestrial-like internal pressure of one atmosphere. This requires the use of thick, heavy walls made of specialized steel or titanium alloys capable of withstanding the pressure at depths of 100 feet or more.

While this design provides a familiar environment for standard servers, it introduces a “thermal bottleneck”. Heat must be transferred from the servers to the internal gas (nitrogen), then from the gas to the hull or internal heat exchangers, and finally to the external seawater. This multi-stage process, while efficient compared to air-cooling on land, is less efficient than direct liquid immersion. Furthermore, the mass of these vessels makes deployment and retrieval a logistically heavy operation.

Pressure-Equalized Pods: The Immersion Frontier

Innovative firms like Subsea Cloud have pioneered a pressure-equalized architecture that eliminates the need for thick pressure hulls. In this model, the interior of the pod is filled with a dielectric fluid that is maintained at the same pressure as the surrounding seawater.

Engineering Comparison: Pressure Vessel vs. Pressure-Equalized

- Internal Atmosphere: 1 atm Dry Nitrogen (Natick) vs. Equalized Dielectric Fluid (Subsea Cloud)

- Structural Material: Thick Steel/Titanium (Natick) vs. Standardized Modular Shell (Subsea Cloud)

- Primary Cooling Mode: Gas-to-Liquid Heat Exchange (Natick) vs. Liquid Immersion Convection (Subsea Cloud)

- Weight Advantage: High mass for ballast/strength (Natick) vs. Low mass with buoyancy control (Subsea Cloud)

- Depth Rating: Limited by hull strength (Natick) vs. Theoretically unlimited (Subsea Cloud)

The thermodynamic advantage of the pressure-equalized pod is significant. Liquid immersion cooling allows for direct contact between the cooling medium and the server components, facilitating heat transfer rates that are orders of magnitude higher than air or gas. Furthermore, because the internal and external pressures are equal, the pod does not face the “crushing” forces of the deep sea, allowing for deployment at much greater depths and the use of lighter, cheaper construction materials. Subsea Cloud claims that this approach reduces both CapEx and OpEx by up to 80% compared to terrestrial builds.

Thermodynamic Analysis and Thermal Transfer Physics

The cooling efficiency of a UDC is governed by the convective heat transfer coefficient (h) of the surrounding fluid and the thermal conductivity (k) of the heat exchange surfaces. Seawater has a thermal conductivity approximately 25 times higher than that of air, and a much higher volumetric heat capacity, allowing it to absorb and carry away heat far more effectively.

In the Project Natick Phase 2 deployment, Microsoft utilized a passive heat exchange system where internal nitrogen was circulated through radiators cooled by external seawater. This system achieved a PUE of 1.07, meaning that only 7% of the total energy was lost to non-computing tasks, a performance level nearly impossible to achieve in terrestrial facilities that rely on energy-intensive air conditioners and chillers.

The Fouling Factor

A critical challenge in subsea thermal engineering is biofouling. Barnacles, algae, and sea anemones naturally colonize submerged structures, creating an insulating layer that can degrade heat transfer over time. Microsoft’s post-retrieval analysis of the Northern Isles pod showed that while the vessel was covered in marine life, the heat exchange performance remained within acceptable parameters for the duration of the 25-month mission. Future commercial deployments are exploring the use of specialized anti-fouling coatings and copper-nickel alloys to inhibit biological growth and maintain consistent thermal efficiency over a 20-to-25-year lifecycle.

Environmental and Ecological Dynamics: The Localized Footprint

The ecological impact of underwater data centers is a subject of ongoing debate between industry proponents and environmental regulators. While UDCs offer a clear global sustainability benefit by reducing carbon emissions and freshwater usage, their localized effect on marine biodiversity must be carefully managed.

Thermal Discharge and Oxygen Levels

The primary concern raised by environmental scientists is the “heat bubble” created by the discharge of warm water from the data center’s heat exchangers. Discharging water that is even a few degrees warmer than the ambient sea can stress local aquatic life and reduce dissolved oxygen levels, which are critical for fish and other organisms.

Microsoft’s research in the North Sea reported that the water temperature near their prototype increased by only “a few thousandths of a degree” in the surrounding currents. Similarly, Hailanyun (the company behind the Shanghai and Hainan UDCs) reported a temperature rise of less than one degree Celsius, which they characterized as having no substantial impact. However, critics argue that these results may not be representative of larger, high-density AI clusters or deployments in enclosed, shallow waters like the San Francisco Bay.

Acoustic Vulnerability and Security

An unexpected “didn’t work” factor identified in recent research is the acoustic vulnerability of underwater data centers. Water carries sound waves much more efficiently than air, and studies from the University of Florida have shown that certain sonic frequencies, such as those transmitted by underwater speakers or sonar, can induce vibrations in hard drive components, leading to data corruption or physical destruction of the hardware.

This “acoustic sabotage” risk is unique to the maritime environment. Furthermore, the noise generated by the data center’s internal cooling pumps and fans could potentially interfere with the echolocation of marine mammals, although studies on Project Natick found that the shrimp and other marine life on the seafloor actually made more noise than the data center itself.

Economic Analysis: CapEx, OpEx, and Total Cost of Ownership

The financial argument for underwater data centers centers on the decoupling of computational costs from the volatility of terrestrial power and water markets.

CapEx: Manufacturing vs. Traditional Construction

Terrestrial data center construction has seen dramatic cost escalations, with average-sized facilities now costing between $500 million and $2 billion. A significant portion of this investment goes into civil engineering, land acquisition, and the complex HVAC systems required for air cooling.

UDCs shift this paradigm toward a “manufacturing” model. Because the pods are standardized, pre-fabricated modules, they can be produced at scale in a factory setting and deployed in under 90 days. Subsea Cloud estimates that this approach results in a 90% reduction in deployment costs per megawatt compared to land builds.

Infrastructure CapEx Breakdown: Terrestrial vs. Subsea (Estimated $/Watt)

- Electrical Infrastructure: $5.30 – $5.63 for Terrestrial vs. Integrated in Module for Subsea

- Mechanical (Cooling): $2.50 – $3.00 for Terrestrial vs. Passive Hull-based for Subsea

- Civil / Shell: $2.13 – $2.50 for Terrestrial vs. Marine Grade Capsule for Subsea

- Total Infrastructure CapEx: $12.50 – $14.66 for Terrestrial vs. Projected 80% Lower for Subsea

OpEx: The Cooling Dividend

The most significant operational advantage of a UDC is the elimination of the “cooling bill”. In a typical land-based facility, cooling accounts for 30% to 40% of the total energy cost. In an underwater environment, this cost is virtually zero, as heat is dissipated passively through the ocean. Furthermore, the 8x improvement in hardware reliability reported by Microsoft suggests that long-term maintenance costs and hardware replacement cycles could be significantly reduced, provided the “retrieval tax” can be managed through modular design or surface-access architectures.

Regulatory Red Tape and the Geographic Filter

A major differentiator between the “worked” and “didn’t work” aspects of UDCs is the regulatory environment. The maritime domain is a complex patchwork of jurisdictional authority, environmental protections, and commercial maritime law.

Western Stagnation vs. Eastern Acceleration

In the United States, the NetworkOcean attempt to deploy in San Francisco Bay was halted by a regulatory “alphabet soup” including the BCDC, the Regional Water Quality Control Board, and the US Army Corps of Engineers. Regulators raised concerns about the impact on eelgrass beds and the endangered delta smelt, and the requirement to prove that “no suitable location exists on land” created a high barrier to entry.

China, by contrast, has leveraged its Pilot Free Trade Zones and the “Blue Economy” mandate to fast-track UDC development. By treating subsea data centers as a strategic national priority, China has been able to integrate these projects into larger offshore industrial estates that combine renewables, aquaculture, and digital infrastructure. This regulatory clarity has been a decisive factor in China’s move from demonstration to full-scale commercial operation.

Marine Engineering and Material Science: The 25-Year Challenge

The viability of a UDC over a 25-year operational lifespan, the industry standard for infrastructure, depends on advanced materials science to resist the hypersaline Pacific or Atlantic environments.

Corrosion Mitigation and Structural Integrity

The Department of Defense spends approximately $20 billion annually on maintenance due to corrosion, highlighting the severity of the challenge. For UDCs, the use of specialized coatings and alloys is not optional.

- High-Entropy Alloys: Composition design utilizing elements like Cr, Ni, and Mo allows for the formation of stable passive films that protect against pitting and crevice corrosion in chloride-rich environments.

- Glass-Flake Coatings: Applied to the exterior of pressurized steel cabins, these coatings provide an impermeable barrier to seawater, extending the structural life of the vessel.

- Underwater Concrete Repair: For UDCs that utilize concrete docking structures, prompt application of repair technology is essential to address the inevitable cracking and degradation caused by hydrostatic stress.

Failure to manage these material risks can lead to catastrophic hardware loss. However, the use of these advanced materials adds to the upfront CapEx, creating a “cost-reliability” curve that operators must navigate.

Geopolitical Implications: The Maritime Data Fortress

Underwater data centers are increasingly viewed as a tool of geopolitical power. As the digital economy becomes the backbone of national security, the physical and cyber-security of the “cloud” takes on a maritime dimension.

AI Dominance and Infrastructure Security

The race for AI dominance depends on access to massive compute clusters that are resilient to both physical attack and environmental disaster. Submarine data centers offer a level of “security by isolation” that terrestrial centers lack. Placed at depths of 250 feet, accessing these facilities requires specialized vessels, ROVs, or deep-sea divers, making them much harder to tamper with than a typical land-based warehouse.

China’s pioneering projects in the South China Sea are seen as the first step toward a “maritime data fortress,” where critical AI infrastructure is protected by both the ocean and the nation’s maritime defenses. This creates a new frontier in the strategic competition between major powers, where control over the “undersea cloud” becomes as important as control over submarine cables.

Synthesis and Future Trajectory

The comparison of global underwater data center initiatives reveals that the technology “works” remarkably well as a solution for cooling efficiency and hardware reliability, but “didn’t work” as a direct drop-in replacement for the agile, high-maintenance model of traditional hyperscale cloud providers.

Project Natick established the gold standard for subsea metrics, PUE of 1.07 and 1/8th the failure rate of land. However, it also highlighted the logistical friction of the sealed-vessel architecture. China has successfully navigated these challenges by scaling up modular clusters in government-protected maritime zones and integrating them with offshore renewable energy.

The future of the field likely belongs to two emerging models:

- Pressure-Equalized Immersion Pods: These offer the lowest TCO and the greatest depth flexibility, making them ideal for long-term, high-density AI training workloads that do not require frequent human intervention.

- Floating/Barge-Based Facilities: As exemplified by Nautilus Data Technologies, these facilities provide the benefits of seawater cooling and zero freshwater usage while maintaining the accessibility and upgradeability of terrestrial sites.

As AI workloads continue to surge and terrestrial resources strain to accommodate hyperscale growth, the ocean remains the most efficient environment ever built for computing. The success of the next generation of UDCs will depend on the industry’s ability to balance the pristine reliability of the subsea environment with the dynamic, modular agility demanded by the AI revolution. The lessons from the first decade of underwater experiments have paved the way for a more sustainable, ocean-cooled digital future.