Why data center power capacity is locked far ahead of demand

At first glance, the practice appears inefficient. Across global markets, large blocks of power capacity for data centers are reserved years before a single server begins drawing electricity. In regulatory filings and utility planning documents, these commitments show up as megawatt-scale loads that may remain largely unused during early project phases.

However, this apparent mismatch between reservation and consumption reflects structural realities rather than miscalculation. Modern digital infrastructure expands at a pace that power systems cannot immediately match.

Over recent years, this sequencing has become more visible. As cloud adoption deepens and artificial intelligence reshapes compute demand, the gap between contracted capacity and actual load has widened. What looks like excess in early stages often functions as a deliberate buffer against grid inertia, forecasting error, and reliability risk.

To understand why early reservation persists, it is necessary to examine how power systems are planned, how demand uncertainty is managed, and how risk is distributed among developers, utilities, and regulators.

Power arrives slower than compute

Digital services scale rapidly once capital and hardware align. Cloud regions can deploy new workloads within months. AI clusters, when chips and networking are available, can ramp even faster. By contrast, reserved power capacity depends on infrastructure that advances far more slowly.

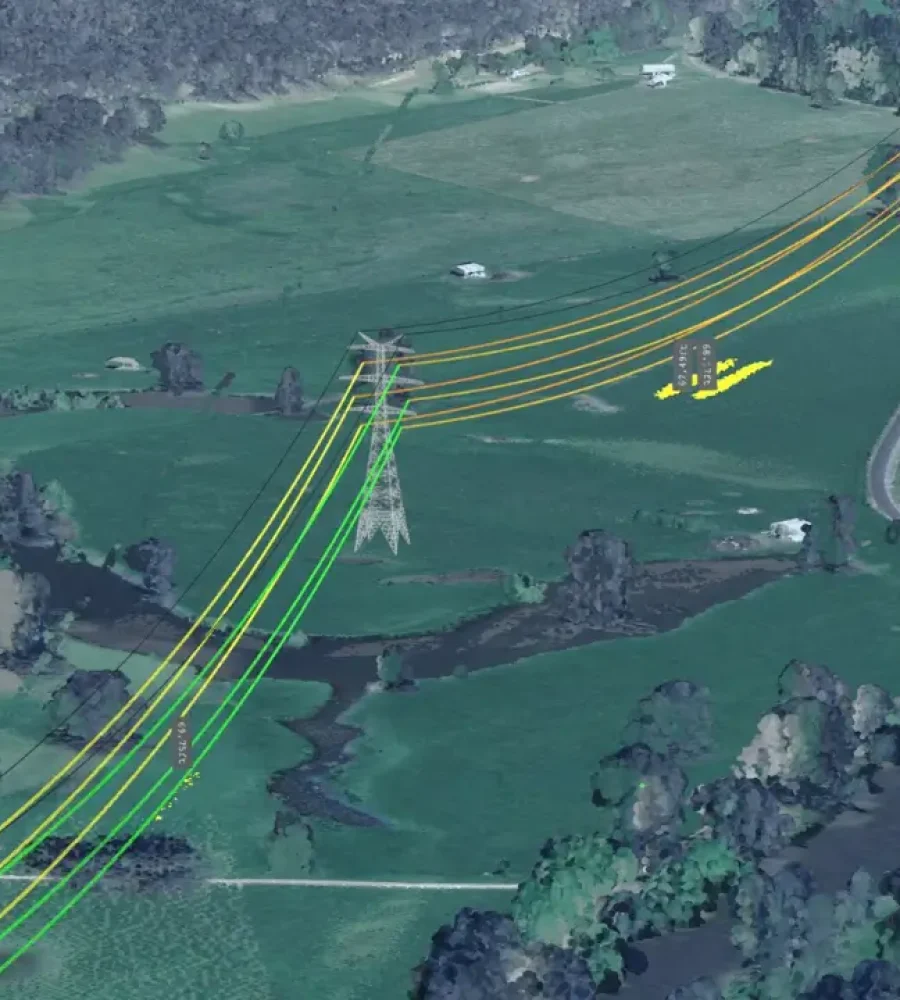

High-voltage substations require extensive design, permitting, and construction. Transmission upgrades involve environmental review, land access negotiations, and system-impact studies. Large power transformers often face procurement lead times stretching several years. Each stage introduces delay that cannot be compressed without compromising reliability.

In practice, electricity must be available before compute arrives. Consequently, power becomes the longest critical-path dependency in the development timeline.

As a result, developers initiate power planning earlier than most other activities. Land acquisition can proceed while permits are reviewed. Buildings can be designed while tenants negotiate contracts. Data center power capacity, however, must be locked in well ahead of commissioning because the grid cannot accelerate on demand.

Capacity reservation is not consumption

Confusion often arises from equating reservation with consumption. Contracted data center power capacity does not indicate that electricity flows at full levels from day one. Instead, it defines the maximum load a facility may eventually draw once fully built out.

In operational terms, most data centers ramp gradually. Initial phases activate a limited number of halls. Subsequent phases come online as tenants deploy equipment. Throughout this process, actual electricity demand increases in steps rather than all at once.

Even so, the grid must be engineered to support the eventual peak from the start. Partial readiness is not an option in power-system design. Substations, feeders, and protection systems must already be capable of handling full load, regardless of current utilization.

For that reason, utilities assess data center power capacity requests against worst-case assumptions. Although early-year meters may show modest draw, the reserved capacity determines how infrastructure is sized and reinforced.

The economic logic behind unused data center power capacity

Unused capacity is frequently described as stranded. While the term suggests waste, it more accurately reflects how risk is allocated. Grid infrastructure requires substantial upfront investment, and utilities need confidence that future demand will justify that spending.

Early reservation of power capacity shifts uncertainty toward the customer rather than the broader rate base. Developers commit financially to capacity that may not be fully utilized immediately. Utilities, in turn, gain the certainty required to proceed with construction. Regulators often favor this model because it limits speculative grid expansion.

From the developer’s perspective, carrying unused capacity can be less costly than facing future scarcity. Compute hardware depreciates rapidly. Power access does not. Securing the capacity early protects projects from congestion, price escalation, or outright denial later.

As a result, what appears inefficient in the short term often represents a rational hedge against long-term constraint.

Forecasting risk in data center power capacity planning

Forecasting has always shaped infrastructure decisions. Recently, however, forecasting large-scale data center power load has become materially more complex. Traditional enterprise computing followed relatively stable growth paths. Cloud migration disrupted that stability. Artificial intelligence has added further volatility.

AI workloads do not scale smoothly. Training clusters can emerge quickly when chips, capital, and network capacity align. Conversely, deployment schedules can slip when supply chains tighten or funding conditions change. Consequently, long-range demand projections now include wider error bands than in prior cycles.

Because underestimating demand carries structural consequences, developers tend to plan toward the upper end of plausible scenarios. Reserving additional data center power capacity absorbs forecasting error without forcing redesigns or new interconnection requests. Although this approach increases early carrying costs, it reduces the risk of stalled expansion.

Utilities respond in parallel. Grid planners apply conservative assumptions to avoid reliability shortfalls. In practice, both sides converge on forecasts that prioritize adequacy over precision.

How interconnection queues reshape data center power capacity behavior

In many regions, the interconnection queue has quietly become the dominant force shaping how data center power capacity is requested. Before electricity can flow, utilities require detailed system-impact studies. These studies evaluate thermal limits, voltage stability, and contingency performance under failure scenarios. Each step consumes time, and each revision can reset review timelines.

Because of that structure, developers rarely approach interconnection incrementally. Instead, full build-out power capacity is often declared at the outset. By doing so, projects reduce the risk of re-entering congested queues later, when grid conditions may be less favorable. Although actual demand may materialize gradually, the contractual request reflects the maximum foreseeable load.

Over time, this behavior has compounded congestion. Large requests accumulate, forcing utilities to model worst-case outcomes across dozens of proposed projects. As queues lengthen, approval timelines stretch further. Consequently, the incentive to reserve early and reserve fully intensifies rather than diminishes.

Rather than signaling speculation, this pattern reflects defensive planning within a constrained administrative system.

Why grid congestion turns data center power capacity into a competitive asset

In established data center markets, grid capacity is no longer abundant. Aging transmission networks, delayed infrastructure investment, and accelerating electrification have tightened available headroom. At the same time, electric vehicles, heat pumps, and industrial electrification compete for the same underlying resources.

Within this environment, data center power capacity functions less like a commodity and more like a gated asset. Projects that secure capacity early gain a durable advantage. By contrast, late entrants often encounter years-long delays or discover that no additional capacity remains available.

As a result, reservation behavior becomes strategic. Developers increasingly prioritize markets where capacity can still be secured, even if near-term utilization remains modest. Over time, this dynamic helps explain why secondary markets attract large early commitments that appear disproportionate to current load.

In practice, scarcity shifts planning from reactive to anticipatory.

Redundancy requirements inflate apparent data center power capacity demand

Another frequent source of misunderstanding involves redundancy. Modern data centers are engineered for resilience rather than minimal capacity. Dual utility feeds, backup generators, and uninterruptible power systems form standard design elements. Each layer contributes to the amount of data center power capacity that appears reserved.

Under normal operations, only part of that infrastructure carries load. During failures or maintenance events, however, alternate paths must support the entire facility. For that reason, each utility feed is often sized to handle full demand independently.

From an external viewpoint, this design appears excessive. From an engineering standpoint, it is mandatory. Reliability standards require systems to withstand equipment failures, extreme weather, and grid disturbances without interruption.

Therefore, redundancy increases preparedness, not consumption.

Planning data center power capacity around worst-case conditions

Power systems are designed around extremes rather than averages. Peak demand, not typical usage, defines system limits. Heat waves, cold snaps, and coincident failures shape engineering criteria.

Because of this reality, utilities evaluate data center power capacity requests using worst-case assumptions. Even if a facility normally operates well below its maximum, the grid must support full load during critical moments. Partial capability would expose the system to unacceptable risk.

Developers mirror this conservatism. Planning around average demand would require retrofits when peaks arrive. Instead, both sides design to the upper bound and accept early underutilization as the cost of reliability.

Unused capacity, in this context, functions as margin rather than miscalculation.

Financial incentives favor early data center power capacity commitments

Financial structures reinforce these technical constraints. Lenders and investors prioritize certainty around essential dependencies. Secured data center power capacity reduces execution risk and supports valuations, even when utilization lags initial projections.

By contrast, projects without firm power commitments face higher financing costs and more conservative underwriting assumptions. Precision in demand forecasting offers limited upside. Underestimating demand, however, can delay revenue generation entirely.

Consequently, capital markets reward early commitment over incremental accuracy. This bias, common across infrastructure sectors, becomes especially pronounced where demand can accelerate rapidly.

Zoning and permitting accelerate power reservation timelines

Power planning rarely occurs in isolation. Zoning approvals, environmental reviews, and municipal permits often hinge on demonstrated infrastructure availability. In several jurisdictions, proof of full data center power capacity at build-out is required before construction can proceed.

As a result, developers secure capacity earlier than operational needs alone would dictate. Doing so prevents projects from stalling during later approval stages. Even speculative developments may reserve capacity to preserve optionality.

In this way, regulatory sequencing pulls power commitments forward in the development lifecycle.

Data center power capacity as a market signal to tenants

Beyond engineering and finance, power availability serves as a signal. Hyperscale tenants routinely screen sites based on whether sufficient data center power is secured. Without that assurance, other site attributes lose relevance.

Early reservation allows developers to market projects with confidence. It reassures tenants that future expansion will not be constrained by grid limitations. As competition intensifies, this signaling effect becomes increasingly important.

Accordingly, capacity functions not only as infrastructure, but also as credibility.

Forecasting uncertainty reshapes data center power capacity decisions

Forecasting demand has always involved uncertainty. In recent years, however, forecasting data center power capacity has become materially more complex. Traditional enterprise computing followed relatively steady growth curves. Cloud migration disrupted that stability. Artificial intelligence has added a further layer of volatility.

AI workloads do not scale smoothly over time. Training clusters can emerge rapidly when chips, capital, and networking align. At other moments, deployment schedules slip because of supply-chain constraints or funding shifts. Consequently, long-range demand projections now carry wider error bands than in earlier cycles.

Given these conditions, developers tend to plan toward the upper range of plausible scenarios. Reserving additional power capacity absorbs forecasting error without forcing redesigns or repeated interconnection studies. Although this approach increases early carrying costs, it reduces the risk of stalled expansion when demand accelerates.

Utilities respond in parallel. Grid planners apply conservative assumptions to avoid reliability shortfalls. In practice, both sides converge on forecasts that emphasize adequacy rather than precision.

How wholesale markets reinforce early data center power capacity commitments

In regions with organized wholesale electricity markets, large loads influence planning well beyond the point of interconnection. Declared data center power capacity feeds into resource adequacy models, reserve margin calculations, and long-term transmission planning.

Once incorporated, these assumptions become difficult to reverse. Reducing declared load after infrastructure approvals complicates procurement schedules and investment decisions. As a result, market operators favor stable, forward-looking commitments.

From a developer’s perspective, early declaration ensures that future growth is already embedded in system plans. Attempting to expand later may trigger new studies or encounter resistance if margins tighten. Consequently, wholesale market design unintentionally rewards conservative, upfront capacity requests.

Asymmetric risk favors over-reserving data center power capacity

Infrastructure planning carries inherent asymmetry. Expanding capacity later often requires new equipment, new approvals, and new construction. Contracting capacity, by contrast, rarely reverses sunk investment.

Utilities face similar trade-offs. Once substations and transmission assets are built, they remain in service regardless of utilization. The greater risk lies in insufficient capacity during periods of peak demand or system stress.

Given this asymmetry, conservative reservation becomes a rational response to uncertainty.

Accountability unfolds across mismatched timelines

Responsibility within the power system is distributed unevenly across time. Developers are accountable for meeting tenant needs years into the future. Utilities are accountable for maintaining reliability on a daily basis. Regulators answer to public and political pressures that shift over shorter cycles.

Early reservation of data center power capacity aligns these timelines. Developers demonstrate foresight. Utilities justify long-lived investments. Regulators can point to firm commitments when approving infrastructure expansion.

Delaying commitment would concentrate accountability at the moment of failure rather than distributing it across planning stages. Few stakeholders prefer that outcome.

Environmental objectives complicate data center power capacity planning

Sustainability goals introduce additional complexity. Critics often point to unused capacity associated with fossil generation. Supporters counter that early commitments enable cleaner infrastructure to be planned and financed.

Both perspectives coexist. Early reservation of data center power capacity can support investment in renewables, storage, and transmission. At the same time, legacy assets may remain necessary to ensure reliability during transition periods.

Policy design, market structure, and timing determine which outcome dominates. What remains constant is the need for early clarity. Clean energy integration does not remove grid constraints; instead, it raises coordination requirements.

Flexibility remains limited despite experimentation

Calls for more flexible capacity models have grown louder. Proposals include non-firm service, shared infrastructure, and dynamic allocation. While these approaches offer promise, adoption remains uneven.

Data centers place a premium on reliability. Interruptions carry significant economic consequences. As a result, flexibility is often traded away in favor of certainty. Utilities, for their part, must maintain fairness and system stability, which limits selective flexibility.

Incremental reforms continue. However, they operate within the same physical and regulatory constraints that drive early reservation today.

Secondary markets and anticipatory power commitments

As primary hubs become constrained, attention shifts to secondary markets. Even there, early reservation of data center power capacity remains common. Developers recognize that today’s surplus can become tomorrow’s bottleneck.

By securing capacity ahead of visible demand, projects hedge against future congestion. This behavior accelerates development in new regions while importing the same planning dynamics that shaped mature hubs.

In effect, anticipation replaces reaction as the dominant expansion strategy.

Data center power capacity and the anchor-load effect

Large facilities often function as anchor loads within regional power systems. By committing to substantial power capacity, these projects justify infrastructure investments that might not otherwise move forward. New substations, reinforced feeders, and upgraded transmission lines built to serve a single facility frequently expand the grid’s ability to support additional users over time.

From a planning standpoint, this effect complicates assessments of unused capacity. Infrastructure initially sized around one data center may later serve residential growth, industrial development, or electrification of transport and heating. Utilities often account for this spillover potential when evaluating large load requests.

Consequently, early reservation of data center power capacity can influence regional development patterns rather than remaining confined to one project footprint.

Why apparent surplus does not indicate inefficiency

Efficiency metrics vary by context. In manufacturing or logistics, unused capacity often signals waste. In power systems, spare capacity performs a different function. It absorbs volatility, supports growth, and protects reliability during abnormal conditions.

Because grids are engineered around peak demand and contingency scenarios, unused data center power capacity during normal operations is expected. Heat waves, equipment failures, and rapid load ramps all test system limits. Designing infrastructure without margin would expose networks to cascading failures.

Therefore, judging capacity solely by utilization rates obscures its operational purpose.

Public perception gaps around data center power capacity

Despite these engineering realities, public narratives frequently conflate reservation with consumption. Power figures reported in headlines rarely distinguish between contracted rights and actual draw. As a result, communities may perceive immediate strain even when load remains modest.

This gap in understanding can fuel opposition to new development. Policymakers may face pressure to restrict projects based on projected capacity rather than measured demand. Developers, meanwhile, struggle to explain why early commitments do not translate into instant grid impact.

Clearer communication helps bridge this divide. Framing data center power capacity as future planning rather than present load provides essential context.

Media framing versus grid realities

Media coverage tends to emphasize scale because scale is easy to quantify. Megawatts reserved make for compelling figures. Timing, by contrast, is harder to convey succinctly.

Yet timing is central to infrastructure planning. Reserved data center power capacity reflects anticipation, not immediate stress. Without that distinction, reporting risks overstating near-term impacts while understating long-term preparation.

More precise framing would align public discourse with how utilities and engineers assess system conditions.

Why early reservation persists across cycles

Each wave of digital expansion revives concerns about power demand. Nevertheless, the underlying drivers of early reservation remain consistent. Grid expansion continues to move slowly. Demand continues to arrive unevenly. Reliability expectations continue to rise.

As long as these conditions persist, power capacity will be secured ahead of use. Historical cycles reinforce this behavior. Periods of underinvestment leave lasting consequences, while periods of over-preparation fade quietly as demand catches up. Institutional memory favors caution.

Adaptation without fundamental transformation

Utilities, regulators, and developers continue to test incremental improvements. Queue reforms, phased interconnections, and improved forecasting tools aim to reduce friction. Progress occurs, but mostly at the margins.

None of these adaptations eliminate the fundamental timing mismatch. Power infrastructure remains capital-intensive and slow to deploy. Digital demand remains fast and unpredictable. Early reservation of data center power capacity bridges that gap.

Until grids become significantly more modular, adaptation will stop short of transformation.

Data center power capacity as preparation, not excess

Viewed over long horizons, early capacity reservation reflects preparation rather than overreach. It aligns infrastructure investment with anticipated demand, even when utilization lags. It distributes risk across stakeholders and across time.

Unused capacity may appear conspicuous in early years. Over longer periods, it blends into the background as facilities fill and loads stabilize. What once looked excessive becomes merely sufficient.

This temporal perspective explains why the practice endures.

Data center power capacity debates often miss the timeline

Debates about infrastructure strain frequently collapse time into a single moment. Power demand is discussed as though it were static, even though grid planning unfolds over decades.

Grids are not built to satisfy yesterday’s load. Instead, they are engineered to withstand tomorrow’s peaks under adverse conditions. When capacity is reserved early, it reflects that long-term orientation. The apparent gap between reservation and utilization is therefore temporal, not technical.

Understanding this distinction helps clarify why capacity figures alone provide an incomplete measure of system stress.

The physical constraints beneath data center power capacity planning

Electric power systems operate within immutable physical limits. Thermal ratings, voltage stability, and fault tolerance define how networks are designed and operated. These constraints apply regardless of whether demand emerges gradually or suddenly.

Because of this reality, data center power capacity must be planned against conditions that may occur infrequently but carry severe consequences. Extreme weather events, coincident peak demand, and equipment failures all shape infrastructure requirements. Designing solely for average conditions would expose systems to instability.

Consequently, unused capacity exists not because planners misjudge demand, but because grids must remain resilient under rare but critical scenarios.

Why just-in-time logic fails for power infrastructure

Modern supply chains prize efficiency through just-in-time delivery. Power systems cannot function this way. Infrastructure does not arrive in small increments aligned neatly with marginal increases in demand.

Instead, substations, transmission corridors, and transformers must be constructed to handle full load from the outset, even if that load materializes slowly.

Because of this structure, data center power capacity must be secured well before it is fully exercised.

The cost of misjudging data center power capacity

Planning errors carry asymmetric consequences. Overestimating demand leads to higher upfront costs and visible underutilization. Underestimating demand, however, risks outages, delays, and lost economic activity.

The latter outcome carries broader systemic costs, planners bias toward adequacy. Developers mirror that bias when reserving the power capacity. Excess capacity imposes a measurable financial burden. Insufficient capacity imposes operational and reputational damage that is far harder to reverse.

This imbalance shapes decision-making more strongly than theoretical efficiency targets.

Data center power capacity and long-term grid resilience

Resilience has become a central objective for modern power systems. Climate volatility, aging infrastructure, and rising electrification loads all increase operational stress. Within this context, spare capacity provides flexibility during emergencies.

Reserved data center power capacity contributes indirectly to that resilience. Infrastructure built to serve large loads often strengthens the grid as a whole. During contingencies, these assets can support stability beyond their original purpose.

Viewed from this perspective, early reservation supports system robustness rather than undermining it.

Why early reservation remains rational under scrutiny

Criticism of unused capacity often assumes static demand and static technology. Neither assumption holds. Demand evolves in bursts, while technology reshapes how electricity is generated, delivered, and consumed.

As long as uncertainty persists, reserving data center power capacity early remains a rational hedge. It aligns slow-moving infrastructure with fast-moving digital demand. It distributes risk across time and across institutions. It preserves the option to scale when conditions align.

Scrutiny may refine processes, but it is unlikely to overturn the underlying logic.

Framing data center power capacity accurately

Accurate framing improves policy outcomes. Treating reserved capacity as immediate load distorts debate. Treating it as speculative hoarding obscures contractual, regulatory, and engineering realities.

A clearer frame recognizes data center power capacity as a planning instrument. It exists to ensure that when demand arrives, the grid is ready. Until then, its presence reflects preparation rather than excess.

Such framing aligns public discussion more closely with how infrastructure systems actually function.

The enduring gap between data and electrons

At its core, the issue reflects a mismatch between digital ambition and physical systems. Data moves at near-instant speed. Electrons move through networks constrained by physics, geography, and regulation.

It compensates for the inertia of infrastructure in a world where compute demand can surge quickly. Until grids become radically more modular, that bridge will remain necessary.

The paradox of unused capacity, therefore, is not a temporary anomaly. It is a structural outcome of modern scale.

Closing perspective on data center power capacity

Understanding why data centers demand power capacity long before it is fully used requires abandoning narrow utilization metrics. Reserved capacity is electricity anticipated, not electricity wasted.

These reservations reflect deliberate choices made under uncertainty, shaped by engineering constraints and institutional incentives. As digital growth continues to accelerate, those choices will remain central to how power systems evolve.

The gap between reservation and utilization may persist. Its purpose will remain unchanged: ensuring that when demand arrives, the grid is ready.