The Compute-Carbon Paradox

The global advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) has triggered a profound structural shift in energy demand. As a result, a fundamental tension has emerged between exponential growth in computational needs and the physical limits of the existing electrical grid.

As of early 2026, the hyperscale data infrastructure sector has become a primary driver of national energy policy and deployment strategies in the United States. Consequently, technology firms now influence timelines and technological preferences for clean energy generation. This marks a clear departure from traditional utility-led planning.

At the center of this transition lies the “Compute-Carbon Paradox.” The same firms driving the AI revolution must also meet aggressive decarbonization mandates. However, their rising energy consumption threatens to undermine those very commitments.

Global data center electricity consumption reached approximately 415 terawatt-hours in 2024. That figure represented 1.5% of total global demand. However, projections show that consumption will more than double to roughly 945 terawatt-hours by 2030. AI training and inference will drive most of this growth.

To sustain expansion at this scale, hyperscale operators require firm, 24/7 carbon-free power. Intermittent renewables such as wind and solar cannot meet this need alone. Without cost-effective storage, they cannot guarantee continuous supply. Therefore, nuclear energy has moved to the center of the strategic roadmap for cloud and AI infrastructure providers.

Department of Energy (DOE) Categorical Exclusion

On February 2, 2026, the Department of Energy established a Categorical Exclusion for advanced nuclear reactors. This decision serves as a critical regulatory catalyst. Specifically, it allows certain advanced reactor projects to bypass lengthy Environmental Impact Statement reviews.

Eligible projects include small modular reactors (SMRs), microreactors, and Generation IV designs. By accelerating environmental approvals, the federal government has aligned nuclear deployment timelines with the rapid build-out schedules of data center campuses. As a result, advanced nuclear technology has shifted from theoretical planning to executable strategy. This shift enables the development of integrated “energy-compute” hubs.

This report finds that the fusion of nuclear and data infrastructure is reshaping the capital stack for energy projects. Long-term power purchase agreements from credit-worthy hyperscalers now function as bankable assets. Consequently, they attract significant private capital.

At the same time, federal tax incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) provide an economic floor for first-of-a-kind deployments. However, risks remain. Concerns persist regarding environmental review transparency, spent fuel management, and volatility in the domestic High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) supply chain.

Looking ahead to 2030, the United States appears poised to package advanced nuclear and AI infrastructure as a sovereign export. In turn, policymakers aim to strengthen global competitiveness and reinforce national security.

The Regulatory Pivot: DOE’s Categorical Exclusions

The regulatory landscape for nuclear energy changed significantly on February 2, 2026. On that date, the Department of Energy established a new Categorical Exclusion for advanced nuclear reactors. Identified in DOE procedures as Appendix B, B5.26, this action alters how the National Environmental Policy Act applies to advanced reactor projects.

The new framework governs authorization, siting, construction, operation, reauthorization, and decommissioning. By streamlining these processes, the DOE aims to accelerate technologies essential to the digital economy’s rising power demand.

Mechanics of the New Categorical Exclusion

Under traditional NEPA requirements, nuclear projects typically require either a full Environmental Impact Statement or an Environmental Assessment. The EIS process, in particular, can prove burdensome. It often involves years of data collection, public hearings, and inter-agency coordination. In many cases, timelines stretch between three and seven years.

The new Categorical Exclusion changes this dynamic. The DOE can now issue a brief determination explaining why a streamlined process applies. If a project meets defined criteria, the agency can bypass the lengthy EA and EIS steps.

The DOE supports this exclusion with a Written Record of Support. In that record, the agency argues that advanced reactors incorporate inherent safety features that distinguish them from traditional light-water reactors.

The exclusion applies when the DOE determines that specific attributes sufficiently reduce risk. These attributes include reactor design, fuel type, operational plans, and bounded fission product inventories. Projects must also demonstrate that they can manage hazardous waste, radioactive waste, and spent nuclear fuel under existing regulatory requirements.

Additionally, the framework allows multiple reactors within a single facility to qualify under the same exclusion. Therefore, developers can pursue large-scale SMR campuses more efficiently.

Key Features of the B5.26 Categorical Exclusion

- Qualifying Reactors: Includes SMRs, microreactors, Generation IV systems, and specific Gen III+ designs.

- Applicable Activities: Covers authorization, siting, construction, operation, reauthorization, and decommissioning.

- Safety Threshold: Projects must minimize off-site dose consequences from the release of radioactive or hazardous materials.

- Legal Basis: DOE grounds the exclusion in agency experience, current technologies, and accepted industry practices.

- Exclusionary Conditions: Projects must not involve extraordinary circumstances that could cause significant environmental effects.

Strategic Implications of the Policy Shift

The primary significance of this regulatory pivot lies in reduced schedule risk and lower front-end carrying costs for developers. Previously, hyperscale data center operators worked within three-to-five-year planning horizons. However, the traditional seven-year NEPA timeline for power generation created a prohibitive barrier.

The CATEX compresses advanced reactor deployment into a timeframe that aligns with AI supercluster construction. As a result, developers can coordinate energy and compute build-outs more effectively. This alignment is especially critical when the DOE serves as the action agency. Such cases include projects seeking DOE loans, site authorization at national laboratories, or DOE-backed power purchase arrangements.

Moreover, the policy shift reflects a broader restructuring of federal permitting. In January 2026, the Council on Environmental Quality rescinded certain NEPA regulations. It replaced them with agency-level guidance that grants greater latitude to departments such as the DOE. Consequently, the DOE can now craft and refine its own procedures.

This regulatory flexibility allows the agency to adjust the CATEX as it gains experience with rapid, high-volume reactor deployments. Furthermore, the policy aligns with Executive Order 14301. That order directed the Energy Secretary to reform or expedite environmental reviews for nuclear testing and deployment.

However, the DOE deliberately placed the CATEX outside the Code of Federal Regulations. This decision carries legal risk. Critics may argue that the department failed to follow procedures required under the Administrative Procedure Act. As a result, litigation could emerge.

To mitigate that risk, the DOE published a comprehensive written record of support. In addition, it solicited public comments through March 2026. These steps help build a defensible administrative record.

The Power Hungry: Why Hyperscalers Need Nuclear

The convergence of AI and energy infrastructure stems from the physical realities of high-performance computing. Modern hyperscale facilities that support AI workloads demand extreme power density and near-perfect reliability. Increasingly, traditional grids and renewable portfolios struggle to meet those requirements alone.

Demand Dynamics and Renewable Limitations

Hyperscale operators have contracted more than 50 GW of renewable energy to meet sustainability commitments. Nevertheless, wind and solar generation remain intermittent. This intermittency creates a persistent operational gap.

AI model training runs require continuous, high-intensity computing. These workloads often last weeks or even months without interruption. Therefore, operators need sustained high-power loads around the clock.

Renewables alone cannot reliably deliver 24/7 firm power at this scale. Meanwhile, current battery storage technologies lack the capacity to support gigawatt-scale AI factories. As demand accelerates, this reliability gap becomes more pronounced.

In contrast, nuclear power delivers carbon-free baseload generation. Plants typically operate at capacity factors exceeding 90%. This reliability directly supports the rapid rise in rack density.

Traditional enterprise data centers operate at 10–15 kW per rack. However, advanced AI clusters now demand 80–150 kW per rack. Some next-generation configurations approach 240 kW per rack. Consequently, operators must secure massive electricity supply within compact geographic footprints.

This power concentration aligns closely with the output profile of small modular reactors and restarted conventional reactors. Therefore, nuclear energy offers a structurally compatible solution.

Corporate Nuclear Strategies and Partnerships

Hyperscalers have moved beyond conventional energy purchasing. Instead, they now enable nuclear restarts and advanced reactor development directly. Several multi-billion-dollar agreements illustrate this shift.

Microsoft and the Crane Clean Energy Center

Microsoft signed a 20-year power purchase agreement with Constellation Energy to restart Unit 1 of the Three Mile Island nuclear plant, now renamed the Crane Clean Energy Center. Through this agreement, approximately 835 MW of carbon-free power will return to the PJM grid by 2027 or 2028.

Microsoft reportedly agreed to pay above-market rates to secure reliable, emissions-free electricity. The company intends to offset data center consumption across the Mid-Atlantic region.

The restart requires significant upgrades to turbines, generators, and cooling systems. Altogether, Constellation plans to invest roughly $1.6 billion. By refurbishing existing infrastructure, the partners avoid the longer timelines associated with new construction.

Google’s Diversified Nuclear Portfolio

Google has adopted a dual strategy. On one hand, it supports the restart of existing nuclear assets. On the other, it pioneers advanced reactor development.

In October 2025, Google signed a 25-year agreement with NextEra Energy to support the restart of the Duane Arnold Energy Center in Iowa. This restart will provide 615 MW of clean power for Google’s cloud and AI infrastructure.

Beyond restarts, Google partnered with Kairos Power to deploy up to 500 MW of fluoride salt-cooled SMR capacity by 2035. The first unit is expected online by 2030.

Furthermore, Google provided early-stage capital to Elementl Power to prepare three additional advanced reactor sites. Each site targets at least 600 MW of capacity. Together, these initiatives create a diversified nuclear portfolio.

Meta and the Prometheus Supercluster

In January 2026, Meta announced a series of nuclear energy agreements to power its Prometheus AI supercluster in New Albany, Ohio. Collectively, these agreements support up to 6.6 GW of new and existing clean energy by 2035.

Meta partnered with Vistra, TerraPower, and Oklo. Its agreement with TerraPower funds two Natrium units targeted for completion by 2032. In addition, Meta secured rights to energy from up to six additional units by 2035.

Moreover, Meta plans to purchase power from Oklo’s Aurora Powerhouse reactors. It will also source electricity from Vistra’s existing nuclear fleet in Ohio and Pennsylvania. That fleet includes Beaver Valley, Perry, and Davis-Besse.

Through this multi-provider structure, Meta reduces concentration risk while securing long-term supply.

Major Hyperscaler Nuclear Initiatives

- Microsoft: Restart of TMI Unit 1 delivering 835 MW through a partnership with Constellation Energy.

- Google (Restart): Duane Arnold restart delivering 615 MW for AI infrastructure in Iowa via NextEra Energy.

- Google (SMR): Deployment of up to 500 MW by 2035 across multiple units with Kairos Power.

- Meta: Multi-provider portfolio supporting up to 6.6 GW by 2035 with Vistra, TerraPower, and Oklo.

- Amazon: Development of four advanced SMRs totaling 320 MW with X-energy and Energy Northwest.

- Oracle: Plans for a gigawatt-scale data center campus powered by three SMRs.

Financing the “Nuclear Renaissance” 2.0

The current resurgence of nuclear energy is distinguished by a transition from government-led funding to co-investment models driven by private tech capital. Hyperscalers are not only signing PPAs but are also acting as cornerstone investors in the capital stack for advanced nuclear developers.

Bankability of Hyperscale Power Purchase Agreements

The long-term PPAs signed by companies like Microsoft and Meta serve as fundamental bankable assets. Because these tech giants have massive balance sheets and a long-term need for power, their commitments allow nuclear developers to secure construction finance that was previously unavailable for first-of-a-kind (FOAK) designs. For example, Meta’s agreements with Oklo and TerraPower provide these companies with the “business certainty” required to raise capital for their demonstration and commercial units. This shift represents a move toward a “merchant-plus” model, where the revenue from a hyperscale contract provides the stability needed for debt financing while allowing the project to potentially export surplus power to the grid.

Impact of U.S. Tax Incentives

Federal tax policy under the Inflation Reduction Act has fundamentally improved the economics of nuclear projects. New nuclear facilities placed in service after December 31, 2024, are eligible for technology-neutral credits under Sections 45Y and 48E.

- Section 45Y (Clean Electricity Production Tax Credit): Provides a PTC of $1.5$ cents/kWh (adjusted for inflation) for the first 10 years of operation, provided prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements are met.

- Section 48E (Clean Electricity Investment Tax Credit): Offers a 30% ITC on the project’s qualified basis.

- Bonus Adders: Projects can receive 10% bonus credits for using domestic content or for being located in “energy communities”. The 2025 OBBBA Act added a specific bonus for “advanced nuclear facilities” in metropolitan areas with historical nuclear ties.

A critical feature of these credits is their transferability. Developers can sell these tax credits for cash to unrelated taxpayers, which provides immediate liquidity to fund construction. This has led to the emergence of nuclear fintech and venture capital entities that specialize in managing these complex capital stacks. For instance, X-energy raised approximately $700$ million in a Series D round in November 2025, with participation from Amazon’s Climate Pledge Fund and other private equity firms, demonstrating the growing appetite for nuclear investment.

Evolving Capital Structures and MLPs

The 2025 OBBBA Act introduced further financial innovations by allowing companies that generate electricity from advanced nuclear facilities to be structured as Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs) starting in 2026. This structure allows for pass-through taxation, making nuclear projects more attractive to a broader range of yield-seeking institutional investors. The shift toward MLPs and private tech capital marks the end of the era where nuclear energy was seen as a purely public-sector or utility responsibility. Instead, it is becoming a core component of the industrial real estate and high-tech capital markets.

Technical Alignment: Synergies of Siting

The physical integration of advanced nuclear reactors with hyperscale data infrastructure offers substantial engineering and operational advantages. These synergies range from shared thermal management to the bypassing of grid constraints through “behind-the-meter” deployment.

Shared Thermal Management and Efficiency

Both nuclear reactors and data centers generate massive amounts of heat. In traditional nuclear plants, roughly two-thirds of the thermal energy is lost. Advanced SMR designs, however, allow for the capture and reuse of this excess energy. When co-located with data centers, this waste heat can be repurposed for industrial processes, district heating, or greenhouses, potentially raising the overall site efficiency to 80% or 90%.

In Finland and Sweden, projects are already underway to recycle waste heat from data centers into municipal district heating networks. For example, Microsoft’s data center region in Finland is expected to heat the city of Espoo, while Google’s Hamina facility provides 80% of the local heat demand. When paired with a nuclear reactor, the data center cooling infrastructure can also serve as a heat sink, improving the reactor’s thermal cycle and reducing the need for external cooling water, which is a significant concern in arid regions.

Behind-the-Meter (BTM) vs. Grid-Tied Strategies

The primary technical bottleneck for hyperscalers is the lengthy queue for grid interconnection. Major markets face 3-to-7-year delays for new power connections due to transmission limitations. Co-locating nuclear reactors “behind-the-meter” allows data centers to interconnect directly with the generator, bypassing the interstate transmission grid and its associated fees.

Operational Comparison: BTM vs. Grid-Tied Strategies

- Interconnection: BTM involves a direct tie to the generator switchyard, whereas Grid-Tied uses a standard network load connection.

- Timing: BTM allows for faster energization by bypassing grid queues; Grid-Tied is subject to utility and grid operator timelines.

- Cost Profile: BTM avoids transmission fees but has higher upfront site costs; Grid-Tied involves standard tariff-based power costs and grid service fees.

- Resilience: BTM offers independent operation but requires local backup; Grid-Tied relies on grid diversity for backup power.

Engineering teams are now designing “energy park” concepts that integrate multiple generation assets behind a single point of common coupling. These layouts include compact “nuclear islands” supplying firm power to rows of high-density data halls. This model requires specialized site preparation, including nuclear-grade geotechnical characterization and hardened utility corridors to link the reactor modules directly to the data center switchyards.

Predictive Maintenance and AI-Enabled Operations

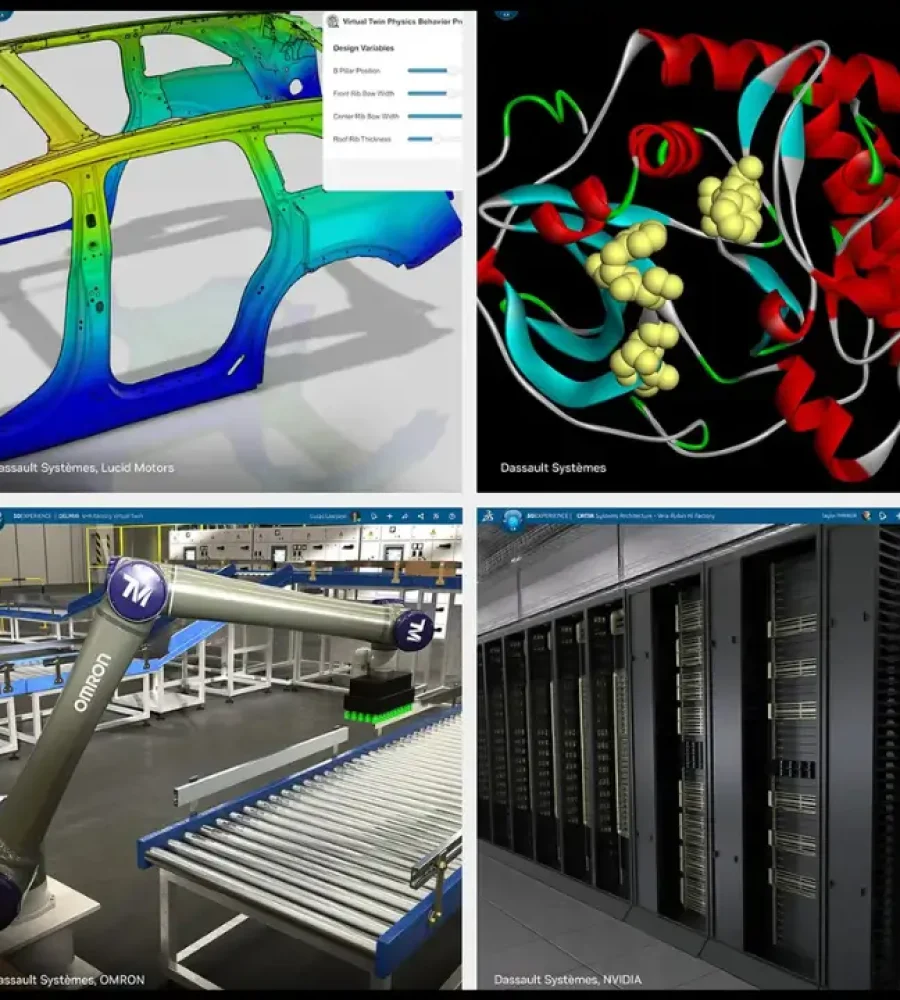

AI and machine learning are being integrated into the operation of the reactors themselves to enhance reliability. AI models can monitor the health of reactor components in real-time, predicting potential failures before they occur and limiting downtime, a proactive approach that is essential for maintaining the 99.999% uptime required by data centers. Furthermore, AI-driven energy management systems can adjust power distribution within the data center based on real-time demand, optimizing the reactor output and reducing waste.

The “Risk” Landscape: Policy and Public Pushback

The rapid alignment of nuclear and AI infrastructure faces a complex array of environmental, regulatory, and supply chain risks that could derail deployment targets if not carefully mitigated.

Environmental Transparency and Public Criticism

The new Categorical Exclusion for advanced reactors has drawn sharp criticism from environmental advocacy groups. Critics argue that the DOE’s move to bypass the EIS process reduces public oversight and transparency. The Union of Concerned Scientists and groups like Beyond Nuclear have expressed concerns that “cutting corners” on environmental reviews for experimental reactors poses risks to public health and safety. Without the public comment periods mandated by traditional NEPA reviews, local communities may feel excluded from the decision-making process, potentially leading to increased local opposition and legal challenges.

Furthermore, some critics question whether advanced reactor designs are truly as safe as the DOE claims. While these designs incorporate passive safety features, they often differ significantly from the earlier prototypes that formed the basis for the DOE’s experience-based determination. The lack of operational data for many of these new technologies remains a point of contention for those calling for rigorous oversight.

Spent Nuclear Fuel Management

The management of spent nuclear fuel remains an ongoing industry challenge with no national repository yet established in the United States. Most nuclear facilities currently rely on on-site dry cask storage, a practice that is expected to continue for the foreseeable future. The Supreme Court’s 2026 denial of petitions regarding interim storage facilities in New Mexico and Texas underscores the legal and political difficulties of waste management.

Hyperscalers and nuclear developers must propose viable on-site storage solutions that comply with NRC regulations. The number of dry casks in the U.S. is projected to exceed 10,000 by 2050, highlighting the growing scale of the problem. While advanced reactors are designed to produce lower waste volumes or repurpose spent fuel, the long-term management of radioactive material remains a primary focus of public pushback.

Supply Chain Risks and HALEU Availability

The success of advanced reactors is heavily dependent on the availability of High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium, which is required by many SMR and Generation IV designs. Currently, there is no large-scale commercial domestic source for HALEU, forcing the U.S. to rebuild its enrichment and conversion capacity from a state of decline. Domestic uranium production has been volatile, with significant quarterly declines reported in 2025.

The U.S. government has initiated programs to restore enrichment capabilities at sites like Paducah and Savannah River, but these facilities are not expected to reach commercial-scale production until later in the decade. Reliance on foreign suppliers, particularly from regions with geopolitical tensions, poses a strategic risk to energy security. Rebuilding this industrial base requires large capital investments and sustained policy support to ensure that advanced reactors have a stable fuel supply.

Strategic Outlook (2027–2030)

The final years of the decade will likely see the first operational milestones for hyperscaler-backed advanced reactors and the emergence of “sovereign AI infrastructure” as a global strategic asset.

Achieving First Criticality

Several advanced reactor projects are on track to achieve “first criticality” with direct or indirect backing from the tech sector.

- Kairos Power: Backed by Google and the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Hermes demonstration reactor is expected to achieve initial operations around 2027. This project serves as a critical testbed for the larger commercial rollout targeted for the early 2030s.

- TerraPower: The Natrium sodium-cooled fast reactor in Wyoming, supported by Meta and Bill Gates, is targeting a 2030 commercial start following its demonstration phase.

- Oklo: Its Aurora Powerhouse reactors, part of the Meta agreement, are aiming for deployment as early as 2030, leveraging fast-reactor technology to provide baseload power to the PJM market.

- NuScale Power: As the first SMR with NRC design certification, its partnership with TVA to deploy up to 6 GW of capacity remains a primary candidate for near-term hyperscale off-take, with first modules delivering power by 2030.

Sovereign AI and Infrastructure Exports

The nexus of advanced nuclear and AI infrastructure is increasingly viewed as an exportable package for governments seeking technological leadership. The 2025-2026 White House executive orders on “Promoting the Export of the American AI Technology Stack” emphasize the importance of building AI capacity on U.S. soil and with U.S.-led energy solutions.

The Department of Commerce is tasked with establishing an American AI Exports Program to support “full-stack” packages that include AI-optimized hardware, data centers, and the nuclear generation required to power them. This approach aims to reduce the global dependence of U.S. allies on infrastructure from adversaries and ensure that American values of “ideological neutrality” and “truth-seeking” are embedded in the AI systems deployed abroad.

National Security and AI Data Centers

AI data centers are being officially designated as “critical defense facilities” in whole or in part when they support national security missions. The Secretary of Energy has been authorized to site and approve privately funded advanced reactors at DOE-owned sites specifically for the purpose of powering these facilities. This integration reinforces the idea that energy and compute are no longer separate commodities but are the combined bedrock of 21st-century national security. By 2030, the United States aims to have at least one operational advanced reactor at a DOE site specifically dedicated to AI infrastructure, setting the stage for a new “Golden Age” of American innovation.

Conclusion

The strategic alignment of advanced nuclear reactors and hyperscale data infrastructure marks a fundamental departure from traditional industrial planning. The massive energy requirements of AI have forced technology firms to become de facto energy developers, using their capital and long-term demand to de-risk a nuclear sector that had struggled for decades to find a viable commercial pathway. The 2026 regulatory reforms provided by the DOE’s Categorical Exclusions have acted as the necessary catalyst, aligning the permit-heavy nuclear industry with the high-velocity cloud sector.

This fusion matters because it creates a blueprint for a decarbonized industrial economy that does not sacrifice computational growth. For infrastructure investors and policy-makers, the actionable insight is that energy and compute have become inseparable. Future capital flows will increasingly prioritize “energy-integrated” campuses that can operate independently of the grid while fulfilling strict zero-emission mandates. However, the path forward requires resolving the structural challenges of the fuel supply chain and waste management to ensure that this nuclear renaissance is sustainable. As the decade progresses toward 2030, the success of this alignment will determine whether the United States can maintain its leadership in both AI and clean energy on the global stage.