The Thermal Crisis of the Artificial Intelligence Era

The rapid transition from traditional cloud computing to the era of generative artificial intelligence has fundamentally changed the physical and thermodynamic requirements of global data center infrastructure. Historically, data centers managed relatively modest heat loads. Server racks typically drew between 5 kW and 10 kW of power. In this setting, air-based cooling and basic evaporative strategies, often using outside air or “free cooling,” maintained operational stability.

The rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) and advanced AI clusters has caused a sharp increase in power density. Modern AI-ready facilities are designed for 30 kW to 50 kW per rack. High-end GPU platforms, such as Nvidia’s latest architectures, already reach 100 kW to 120 kW per rack. Projections are even higher. Industry leaders like Schneider Electric predict next-generation AI racks could require up to 240 kW in less than a year. Nvidia’s 2027-era Rubin Ultra platforms may consume as much as 600 kW per rack.

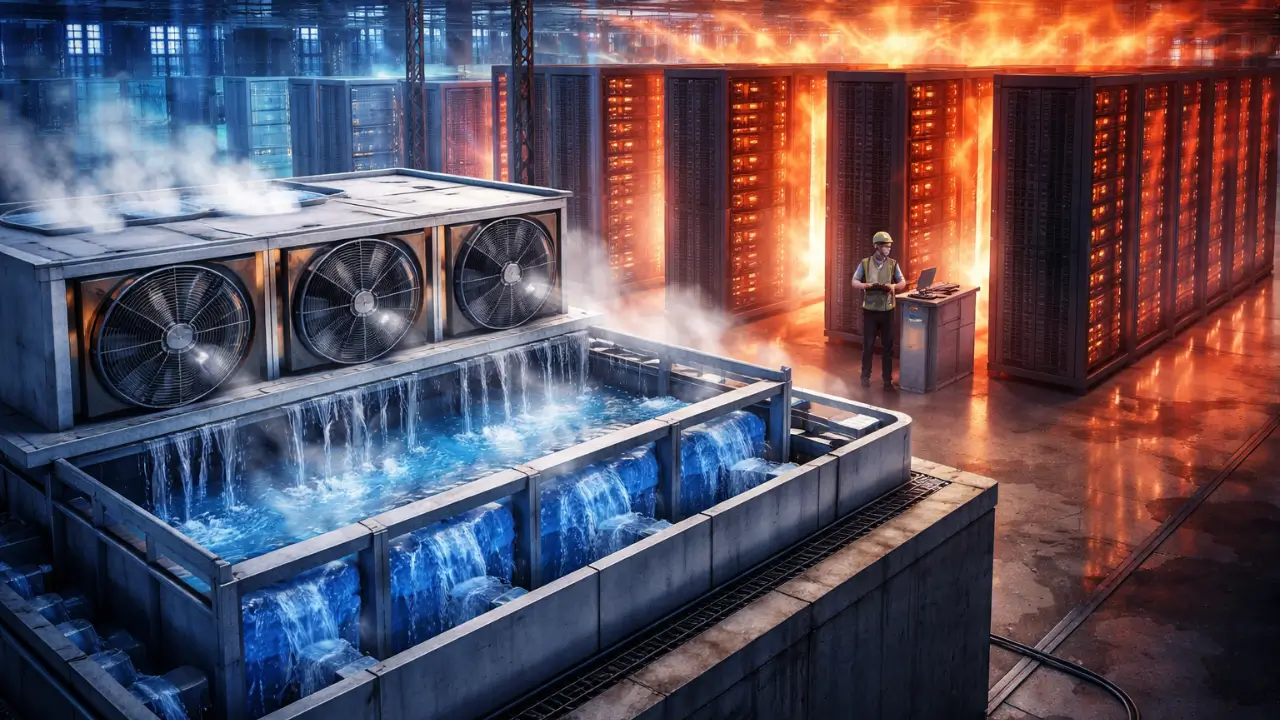

This growth in heat load challenges evaporative cooling, the industry’s preferred method for balancing energy efficiency with low capital costs. Evaporative cooling relies on the latent heat of vaporization, the energy absorbed when water changes from liquid to gas, to remove heat from the data center. While this method is far more efficient than mechanical refrigeration, it is limited by the physical properties of air as a transport medium. As rack densities approach the hundred-kilowatt range, the required air volume becomes physically unmanageable. This results in excessive noise, high fan power consumption, and localized thermal “dead zones.”

The industry stands at a crossroads. Experts are exploring whether innovations in tree-inspired thin-film evaporation can improve this legacy technology or if a full migration to liquid-to-chip and immersion cooling is the only viable path. This report examines the technical, operational, and strategic aspects of this shift. It evaluates whether evaporative systems can adapt to the 100 kW-per-rack reality.

The Physics of Heat Removal: Why Air is Reaching its Limit

The main bottleneck for evaporative cooling is the vast difference in heat-carrying capacity between air and liquid. Air carries roughly 3,300 times less heat per unit volume than water under standard conditions. This fact sets the architectural limits of modern data centers. To move one kilowatt of heat using air with a 10°F temperature rise, a system needs about 100 cubic feet per minute (CFM) of airflow. For a 40 kW AI rack, the airflow requirement rises to 4,000 CFM, producing wind speeds in the cold aisle similar to a Category 2 hurricane.

At 100 kW, the physics becomes unmanageable. A 100 kW rack requires 10,000 CFM of airflow. Generating this air volume demands massive fan arrays that create noise levels above 95 decibels, hazardous to human operators. Fans may also consume up to 25 kW of power, offsetting the cooling efficiency gains. The heat transfer coefficient of air-to-surface convection is limited to 25–250 W/m²·K. In contrast, liquid-to-surface convection reaches 3,000–15,000 W/m²·K. This 60-fold improvement allows for much smaller and more targeted heat exchangers.

Research on power density trends and thermodynamic properties indicates that global capacity demand will grow from 55 GW in 2023 to 200 GW by 2030. This growth is driven by peak chip power ratings, climbing from 150–200 W to over 1,400 W.

Breakthrough in Thin-Film Evaporation: Tree-Inspired Cooling

To overcome the limits of bulk-air evaporative cooling, researchers have shifted focus to micro-scale interfacial heat transfer. Associate Professor Hadi Ghasemi at the University of Houston, leading the NanoTherm Group, has developed a “tree-inspired” thin-film evaporative cooling method. This approach removes heat at least three times more effectively than current industry standards. It addresses a critical bottleneck: in traditional cooling, a liquid layer over a heat source often becomes unstable during evaporation, which reduces its ability to carry heat away efficiently.

The Mechanism of Bio-Mimetic Branching

Ghasemi’s design uses topology optimization and AI modeling to create thin-film structures in branched, tree-like shapes. These structures consist of roughly 50% solid material and 50% empty space. This architecture allows for a high critical heat flux at lower “superheat” compared to conventional structures. In practice, this means the system can remove large amounts of heat without the cooling surface reaching dangerously high temperatures.

The geometry of these micro- and nanostructures primarily controls interfacial heat flux. The UH team found that the optimal width-to-spacing ratio is 1.27 for square pillars and 1.5 for wires or nanowires. This ratio does not depend on the solid material or the thermo-physical properties of the cooling liquid, suggesting a universal strategy for high-performance thermal management. At these optimal ratios, increasing the structure density, by reducing pillar dimensions, directly raises the interfacial heat flux.

Overcoming the Temperature Discontinuity Mystery

A key focus of UH research is the temperature discontinuity at the liquid-vapor interface during evaporation. Molecular-level analysis using the Boltzmann transport equation and Direct Simulation Monte Carlo (DSMC) methods showed discontinuities ranging from 0.14 K to 28 K. These variations depend on the vapor-side boundary conditions. Accurately capturing the interfacial state requires suppressing the vapor heat flux.

This insight enables the design of evaporative membranes that operate near the extreme limits of physics. Laboratory tests show that these fiber membranes can handle heat fluxes of 800 W/cm², a record for systems of this type. By comparison, a typical soldering iron tip operates at around 100 W/cm², and sunlight on Earth provides only 0.10 W/cm². Handling 800 W/cm² allows tree-inspired systems to manage the intense, localized “hot spots” generated by the silicon dies of high-performance GPUs, such as the H100 or Blackwell series.

Microfluidic Evolution: Microsoft’s Bio-Inspired Silicon Etching

While Ghasemi’s research focuses on the membranes, Microsoft has taken a parallel approach. They integrate microfluidic evaporative and liquid cooling directly into the silicon of AI chips. This design removes the multiple layers of thermal interface materials (TIM), heat spreaders, and cold plates that traditionally separate the coolant from the heat source.

AI-Driven Thermal Routing

Microsoft partnered with the Swiss startup Corintis to use AI to map unique heat signatures on a chip. Instead of standard parallel cooling channels, AI optimized a bio-inspired design that mimics leaf veins or butterfly wing patterns. These channels direct coolant more efficiently to high-heat regions, enabling precise thermal management compared to traditional straight-line grooves.

Lab-scale tests show transformative results:

- Heat Removal: Three times the performance of current cold plate technology.

- Temperature Reduction: Maximum silicon temperature rise inside a GPU drops by 65%.

- Heat Flux Capacity: Can dissipate over 1 kW/cm², two to three times more than standard cold plates.

- Coolant Efficiency: Direct contact with silicon means the coolant does not need to be extremely cold, saving significant energy on refrigeration.

This direct-to-silicon microfluidics also enables safer overclocking. Chips can run beyond standard speed ratings without thermal damage, offering a performance edge in competitive AI model training.

Operational Realities: Direct vs. Indirect Evaporative Systems

Despite micro-scale breakthroughs, large-scale deployment of evaporative cooling in data centers faces trade-offs. Operators must balance water efficiency, energy consumption, and equipment reliability.

Direct Evaporative Cooling (DEC)

DEC is a simple and cost-effective method for cooling air. Air passes through a water-saturated medium, and evaporation cools it before it enters server rooms.

- Advantages: Low energy footprint (only fans), simple installation, high efficiency in dry climates.

- Disadvantages: High water usage, potential introduction of outdoor pollutants, and humidity fluctuations. Large-scale DEC requires access to significant potable or reclaimed water sources.

Indirect Evaporative Cooling (IDEC)

IDEC separates indoor air from the external environment using a fluid-cooler and a heat exchanger. Heat from the data center transfers to a cooling fluid, which is then cooled by evaporation in an external air-to-water heat exchanger.

- Advantages: Prevents indoor contamination, maintains humidity control, does not always require potable water.

- Disadvantages: Lower efficiency than DEC and higher complexity due to the extra heat exchange stage.

Adiabatic Cooling as a Hybrid Solution

Adiabatic cooling provides a middle-ground solution for high-density AI environments. These systems operate as “dry coolers” for most of the year to conserve water. During peak ambient temperatures or extreme heat loads, the system activates its wet mode, using water evaporation to pre-cool incoming air.

- Water Conservation: Systems like the EVAPCO eco-Air Series can save up to 95% of water compared to traditional cooling towers.

- PUE Targets: Adiabatic coolers support ultra-low Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE), offering roughly 30% energy efficiency improvement over conventional mechanical cooling.

Case Study: Meta’s AI Infrastructure Overhaul

Meta Platforms offers a real-world example of the shift from air-based evaporative cooling to advanced liquid-centric strategies to support its $65 billion AI investment. Between 2021 and 2024, Meta moved from efficient air and evaporative cooling to a multi-faceted liquid cooling strategy.

Transitioning to Hybrid Liquid-Air Systems

Meta’s new strategy uses different cooling methods depending on regional climate and facility age:

- Air-Assisted Liquid Cooling (AALC): Co-developed with Microsoft, this hybrid system integrates direct-to-chip liquid cooling into older data centers originally designed for air. It serves as a bridge technology, allowing upgrades without a full rebuild.

- State-of-the-Art Precision Liquid Cooling (SPLC): Produces cold water rather than cold air and is over 80% more water-efficient than the average data center.

- Dry Cooling for Arid Regions: Wisconsin and El Paso facilities use dry cooling and closed-loop systems to minimize water use, supporting Meta’s “water-positive” goal for 2030.

AI-Powered Operational Optimization

Meta also uses AI to optimize existing evaporative systems. Simulator-based reinforcement learning (RL) reduces supply fan energy use by 20% and water consumption by 4%. The RL agent tests different supply airflow setpoints in a physics-based thermal simulator to maximize efficiency while keeping cold aisle temperatures within strict service limits.

The Economic Benchmarks of Cooling Transition

Switching from air to liquid-to-chip or immersion cooling changes both capital and operating costs. While liquid cooling is costlier upfront, high-density AI workloads make it the only viable economic solution for many operators.

Capital Expenditure (CapEx) Comparison

Installing liquid cooling is significantly more expensive than air cooling. For a 1 MW facility, liquid cooling infrastructure costs $3–4 million, roughly double the $1.5–2 million for air cooling. Key components include 500 kW Cooling Distribution Units (CDUs) at $75,000–150,000 and server cold plates/manifolds at $5,000–10,000 each.

Liquid cooling also improves “real estate economics.” Air-cooled 40 kW racks require 25 racks per megawatt (2,500 sq ft). Liquid-cooled 100 kW racks need only 10 racks per megawatt (1,000 sq ft). At $200/sq ft per year, this density saves roughly $300,000 per megawatt annually.

Operating Expenditure (OpEx) and Maintenance

Liquid cooling reduces energy costs and extends hardware lifespan. Air-cooled facilities spend about 40% of their energy on cooling. Liquid cooling can cut this by 40%, saving $3–7 million annually for a 10 MW facility at $0.10/kWh. Liquid-cooled servers also last 5–7 years, compared to 3–4 years for air-cooled, potentially deferring $2–3 million per MW in refresh costs over a decade.

Environmental and Policy Challenges: The Water-Energy Nexus

Evaporative cooling faces increasing environmental constraints, especially in water-stressed regions like India and the American Southwest.

The India/Mumbai Crisis Case Study

India’s data center capacity has tripled since 2020 and may reach 6.5 GW by 2030. Water implications are severe:

- Consumption: 150 billion liters used in 2025, expected to double by 2030.

- Localized Stress: A 100 MW hyperscale facility consumes 800,000–2,000,000 liters per day.

- Urban Competition: Mumbai, hosting 25% of capacity, competes with municipal water supplies for over 20 million people.

As of 2026, India is creating a regulatory framework. The 2026 Budget introduced tax holidays for data center investments but emphasizes “frugal AI” and resource-efficient deployment. Only 5 of 15 state policies currently include enforceable water-use efficiency standards.

Global Water Vulnerability

Worldwide, nearly 45% of over 9,000 assessed data centers may face high water stress by the 2050s. Large facilities can require up to five million gallons per day, rivaling small municipalities. This hidden water cost of AI is drawing regulatory attention.

Strategic Outlook: Can Evaporative Cooling Keep Up?

Traditional bulk-air evaporative cooling cannot manage 100 kW+ racks in the generative AI era. However, evaporation at the micro level is evolving.

The Shift to Phase-Change Liquid Cooling

Next-generation cooling uses liquid, not air. Two-phase immersion and microfluidic thin-film systems exploit latent heat without air inefficiencies. Two-phase immersion can handle 150–250 kW per rack, extending evaporation concepts into ultra-high-density AI.

Hybridization as the Default Architecture

Future data centers combine multiple cooling approaches:

- Liquid Cooling (DTC or Microfluidic): Handles 80–90% of heat from GPUs and accelerators.

- Rear-Door Heat Exchangers/In-Row Cooling: Captures residual heat from memory and storage.

- Adiabatic/Evaporative Rejection: External to the data hall, rejects heat efficiently while minimizing water use.

Electrical and Structural Constraints

High-power racks (>50 kW) require massive 240VAC cables, which impede airflow. Shifting to 800VDC reduces current by 70%, shrinks conductors, and cuts copper mass by 80%, enabling dense piping for advanced liquid cooling.

Synthesis and Conclusion

Traditional air-based evaporative cooling is nearing its limits. AI chip power is rising from 700 W to over 1,400 W per chip, creating a thermal wall that air cannot penetrate.

Research in tree-inspired thin-film evaporation and bio-mimetic microfluidics provides a path forward. By moving from bulk to interfacial phase-change cooling, engineers can handle 800 W/cm² to 1 kW/cm²—levels previously seen only in high-energy lasers or aerospace systems.

Evaporative cooling is not obsolete. Instead, it is moving closer to the chip, integrated into microfluidic channels or thin-film membranes. At the facility level, closed-loop adiabatic systems allow efficient heat rejection with minimal water use.

For infrastructure planners, the directive is clear: design facilities for liquid cooling from day one. Relying on traditional air-based systems risks stranded assets, high OpEx, and environmental consequences. The future belongs to hybrid systems that combine molecular-level, chip-level phase-change efficiency with climate-agnostic, water-conscious facility-level rejection. By 2030, AI heat loads will be managed not by moving more air, but by moving heat more precisely using phase-change physics.