Artificial intelligence has become shorthand for the future of productivity, automation and geopolitical competition. Yet beneath the algorithms lies a more grounded question: could AI function without the vast, energy-intensive data centres that now anchor its growth?

The answer, at least for the foreseeable future, is no.

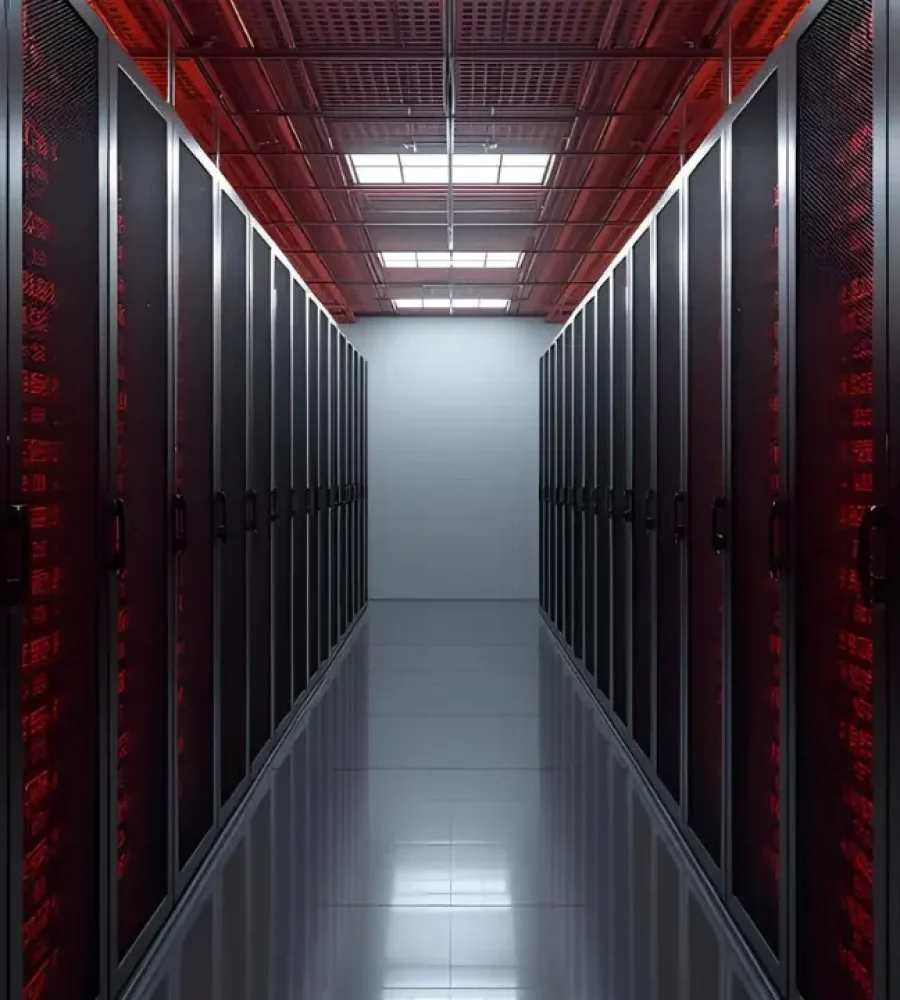

AI systems operate across a spectrum. On one end sit lightweight models running on smartphones, cameras and embedded chips. On the other stand massive training clusters comprising thousands of accelerators operating in synchronised parallel. The latter, not the former, define the frontier of AI capability. And they require concentrated power, cooling and network infrastructure that only large-scale data centres currently provide.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global data centre electricity consumption reached roughly 415 terawatt-hours in 2024, about 1.5% of total global electricity demand. The agency projects that figure could more than double by 2030, driven significantly by artificial intelligence workloads. These projections underscore a simple reality: as AI scales, so does its energy backbone.

The Current State of Data Centers and Their Energy Reality

Large language models and multimodal systems demand sustained parallel computation. Training involves repeated passes through vast datasets, requiring enormous memory bandwidth and tightly coupled accelerators. Distributed edge devices even as they become more capable, lack the physical power density and thermal control to replicate such environments at scale.

This does not mean decentralisation is irrelevant. Edge computing is expanding rapidly. Smartphones now handle voice recognition and image enhancement locally. Industrial IoT systems perform real-time inference without round-tripping to the cloud. Hybrid architectures where devices manage routine tasks while central data centres handle intensive workloads have become standard design practice.

However, decentralisation shifts workload; it does not eliminate the need for centralised compute. Model updates, large-scale retraining and high-throughput inference remain dependent on dense infrastructure.

The current state of data centres reflects that concentration. Hyperscale campuses cluster near robust grid connections and fibre routes, enabling high power density per rack and resilient uptime. Operators pursue efficiency metrics such as Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE), adopt liquid cooling and secure long-term renewable power contracts. Renewable sources account for roughly a quarter to a third of global data centre electricity supply, though the exact share varies by region and reporting methodology. Progress depends not only on facility design but also on the pace of grid decarbonisation.

Efficiency Innovation Within Centralised Infrastructure

Some operators demonstrate how engineering choices can mitigate environmental impact. Google’s Hamina data centre in Finland, for example, uses seawater from the Gulf of Finland for cooling, reducing reliance on energy-intensive mechanical chillers. The facility also integrates heat-recovery systems that redirect waste heat to local district heating networks. Location-specific design, rather than scale alone, defines its efficiency strategy. Such approaches illustrate how infrastructure can evolve without abandoning centralisation.

Meanwhile, research continues into advanced solutions. Liquid and immersion cooling reduce thermal resistance and enable higher rack densities. Companies are exploring high-capacity transmission technologies, including superconducting power lines, to improve energy delivery efficiency within campuses. These developments aim not to replace data centres, but to make them denser, cleaner and more resilient.

Economic incentives reinforce the model. Concentrated facilities allow operators to amortise specialised accelerators across large fleets, streamline maintenance and optimise utilisation rates. Enterprises favour centralised environments for regulatory compliance, security controls and operational consistency. Fragmented compute would complicate governance and increase systemic risk.

Policy, however, may determine how sustainable expansion becomes. Grid bottlenecks, transmission delays and local resistance to large power draws pose constraints. Governments face balancing acts between industrial growth and community energy needs. Strategic grid investment and transparent planning will shape whether AI infrastructure scales smoothly or encounters friction.

The Strategic Path Forward for AI Infrastructure

Looking ahead, technological progress will shift boundaries. Model compression, quantisation and hardware–software co-design will continue improving per-watt performance. More inference workloads will migrate closer to users. Yet breakthroughs at the leading edge where models grow larger and more complex, will continue to require concentrated compute environments.

The notion of AI detached from data centres remains attractive. It suggests a future of ubiquitous intelligence untethered from heavy infrastructure. In practice, AI resembles previous industrial revolutions: distributed applications resting on centralised systems. Just as electrification depended on power stations, advanced AI depends on compute stations.

The strategic challenge, therefore, is not whether to eliminate data centres, but how to power them responsibly. Efficiency gains, renewable procurement, advanced cooling and grid modernisation will determine the sustainability of AI’s trajectory. AI without data centres may serve as a compelling thought experiment. AI without energy infrastructure, however, is not an operational reality.